Ross Douthat is nostalgic for the ’90s, in a viral article, writing:

But as a statement about generational experiences, Alter was basically right. If you were born around 1980, you grew up in a space happily between — between eras of existential threat (Cold War/War on Terror, or Cold War/climate change), between foreign policy debacles (Vietnam/Iraq), between epidemics (crack and AIDS/opioids and suicide), and between two different periods of economic stagnation (the ’70s and early Aughts). If you were born later, you experienced slow growth followed by financial crisis followed by a recovery that’s only lately returned us to the median-income and unemployment stats of … 1999.

And a similar article from Quillette, The End of Aspiration, about the economic realities and hardships facing young people today, compared to past generations:

In the United States, about 90 percent of children born in 1940 grew up to experience higher incomes than their parents, according to researchers at the Equality of Opportunity Project. That figure dropped to only 50 percent of those born in the 1980s. The US Census bureau estimates that, even when working full-time, people in their late twenties and early thirties earn $2000 less in real dollars than the same age cohort in 1980. More than 20 percent of people aged 18 to 34 live in poverty, up from 14 percent in 1980. Three-quarters of American adults today predict their child will not grow up to be better-off than they are, according to Pew.

Few metrics demonstrate the end of aspiration better than the decline in home ownership. The parents and grandparents of the millennial generation (born between 1982 and 2002) witnessed a dramatic rise in homeownership; in contrast, by 2016, home ownership among older millennials (25-34) had dropped by 18 percent from 45.4 percent in 2000 to 37 percent in 2016. Without a home, these millennials will face a “formidable challenge” in boosting their net worth. Property remains central to financial security: Homes today account for roughly two-thirds of the wealth of middle-income Americans; home owners have a median net worth more than 40 times that of renters.

Millennials may be worse-off than earlier generations due to an exceptionally competitive labor market, decreased home ownership, high inflation-adjusted rent, student loan debt, high medical expenses, and lower real wages.

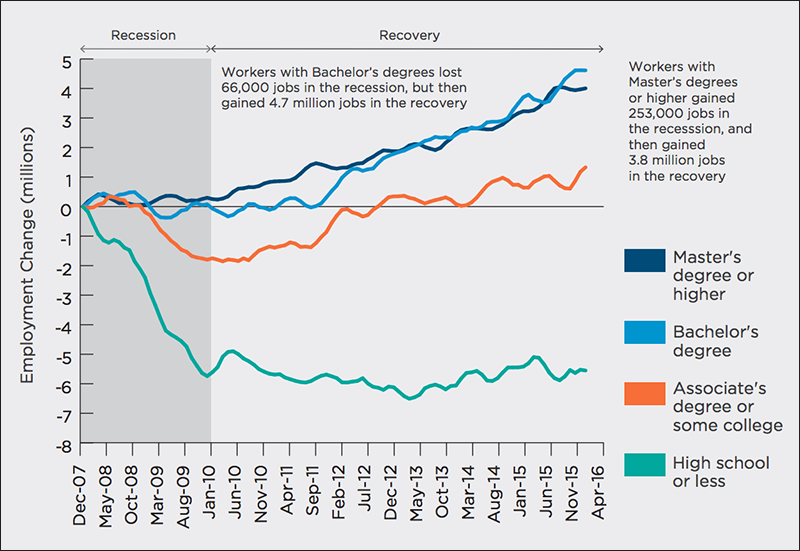

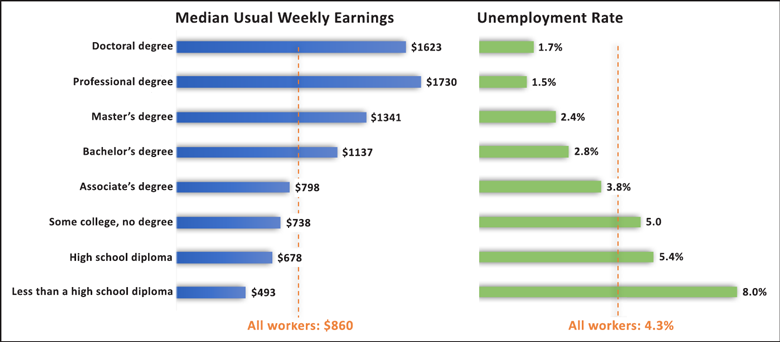

The wage and employment disparity between college grads and high school grads is the widest it has ever been, making college an expensive necessity for advancement into the middle class:

If thus comes as little surprise than that many young people feel nostalgia for the ’90s. Everything seems so competitive these days, both in terms of the job market and higher education. Every year, millions high school students cram for the APs and SATs. Parents collectively spend millions of dollars a year on tutoring and other programs to help get their children into top schools and universities–sometimes by any means necessary, as the most recent college cheating scandal has shown. Despite a very low unemployment rate, employers, especially for good-paying, prestigious jobs, are inundated with applicants. Such a competitive labor markets, in turn, makes college even more competitive and increases the stakes.

And also, and in spite of the absence of actual civil unrest and violence, we live in a nation and political climate that seems more divided and angrier than ever, and Americans trust each other less than ever. Society feels like it’s on the precipice of an all-out class, race, and political war that seems all but inevitable, sorta like the riot scene of the Spike Lee film Do The Right Thing, yet never comes. Instead of trading physical blows, we’re un-friending each other on Facebook over politics, and tweeting invective to signal and foment digital mobs and outrage against individuals and groups that we perceived as having wronged us or of the opposing ideological tribe.

But not only that, but a paternalistic, condescending media–that–rather than elucidating and helping people understand the world, is trying to turn it on itself–and that ascribes the most negative, uncharitable motives and caricatures to the ‘outgroup’ and presupposes its own ineluctable, self-anointed moral superiority in doing so, whether it’s generalizing Trump voters as being motivated by or condoning racism, or the media refusing to admit when it was wrong, such as in 2016 being so certain Trump would lose, or, in 2017-2019, that Trump colluded with Russia and would be impeached.

The media paints Trump supporters with a mile-wide brush, but the the overwhelming majority of Trump supporters are not racist by the conventional definition of the word ‘racism’, which in recent years has been expanded to mean not actual discrimination and prejudice by one racial group against another, but rather individuals that hold beliefs and support causes deemed ‘socially unacceptable’ by what can be described by the so-called ‘regressive left’, who are more interested in labeling, protesting, and accusing than engaging in civil debate. If we want to fix politics, the first thing we can do is to start listening.