Taleb is having another one…

Reframing Christoper's excellent study in terms of much much of life's results ARE NOT explained by IQ test results.

By now the matter should be closed. https://t.co/K58wm9qVaA pic.twitter.com/ZCh5ZuKfm4— Nassim Nicholas Taleb (@nntaleb) January 22, 2025

I already refuted his points 2022, but to reiterate:

1. The claimed low correlation between IQ and job performance or employer satisfaction is conditional on getting the job, which means clearing the necessary screening (e.g. interviews, Wonderlic test, background checks, etc.). All of these act as IQ filters. It’s not like Google picks employees blindly from the general population, unlike McDonald’s workers, who are more representative of the general population. If the carefully screened Google employees were replaced with McDonald’s employees, it goes without saying satisfaction would nosedive. Maybe this comes off as elitist, but such screening exists for a reason–all companies do it, even low-paying ones.

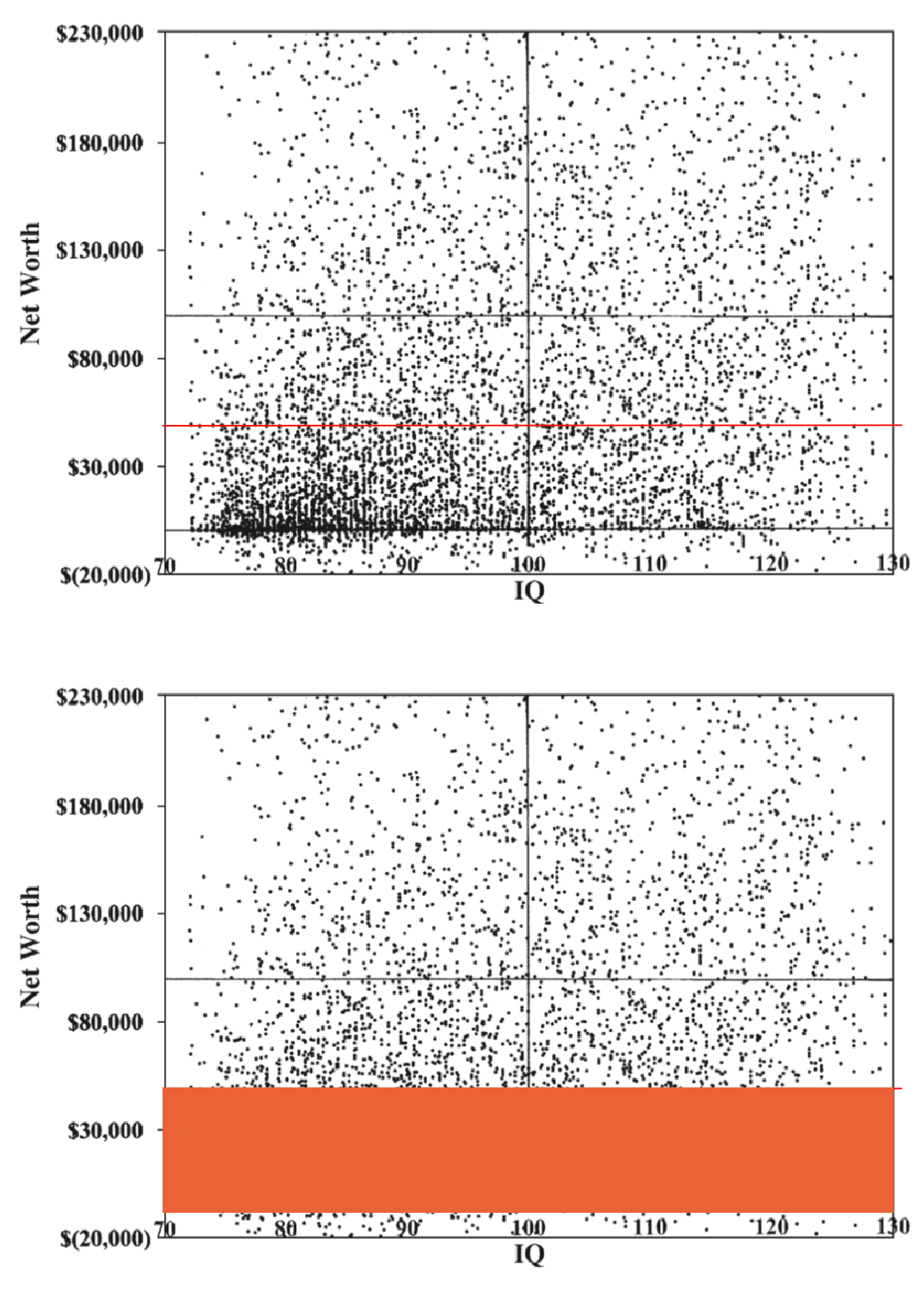

2. I’m sure many have seen the below scatterplot from one of Taleb’s articles or posted on Twitter claiming that IQ does not matter for wealth or income:

It looks convincing, but it overlooks two key factors: First, it’s based off of old data from a 2007 study of data compiled from the ’70s. Second, it does not control for individual preferences.

The obvious confounder is individual preferences. Among individuals who aspire to wealth, having a high IQ helps, among luck and other factors. The high-IQ guy who studies comparative literature is not going to earn as much as the contractor. Thousands of people apply for engineering jobs at Google, Meta, Amazon etc.—the smarter applicants tend to get those jobs. Same for top quant firms like Jane Street. Outlier wealth is a lot to do with luck, but this does not invalidate the role of IQ too, controlling for preferences.

On Reddit’s popular ‘FIRE’ communities (e.g. /r/FatFire) those who achieve financial freedom earliest in life or who earn the most money tend to also have lucrative tech jobs or are early employees at tech start-ups. IQ plays a major role in these. Sure, there is survivorship bias, but high IQ still a necessary condition to get the job at all. ‘Blue collar’ 30/40-year-old multi-millionaire retirees are few and far between. This holds even for less renumerate professions or endeavors. For the comparative lit guy, he’s still competing against others for things like tenure, grad school admissions, or being published in a selective journals–that too requires a high IQ.

Also, smarter people will tend to have more years of schooling and thus may not earn as much initially (or have student loan debt) compared to their peers who enter the job market immediately after high school. But they close the gap and earn more later.

3. Studies claiming a low correlation between IQ and profession, or a low IQ threshold for certain professions, are based off of ’90s or older data (or data from ex-US countries such as Norway, Sweden, or the UK) and thus inapplicable to America’s much more competitive economic landscape today. Ex-US countries tend to be less competitive and have lower wages, so the cognitive filtering is not as strong. From my 2023 article Old studies about income/wealth and job success vs. IQ are unconvincing: Such studies may have been accurate then, but does not generalize or extrapolate to America now.

Recent trends likely point to a stronger correlation of IQ vs career success, due to higher salaries at the tails (e.g. lucrative and highly competitive tech and finance jobs), as well as increased pre-employment screening especially post-Covid. Employers today have more ways than ever to screen applicants, such as automated background checks and resume filtering, checking the applicant’s social media profile, and so on. All of these can be done at scale, fully automated. None of these things existed or were as prevalent in the ’90s.

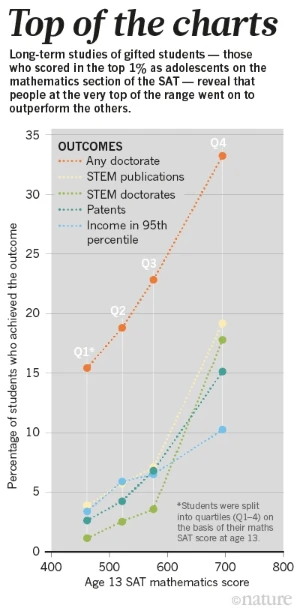

4. There is no evidence to suggest career success, academic achievement, eminence, etc. diminishes with increasing IQ. The oft-claimed 120 IQ threshold of diminishing returns as popularized by Gladwell and others is wrong, especially not for STEM-centric fields. Is it a coincidence that arguably best mathematician in the world, Terrance Tao, is also likely among the smartest? Where is the diminishing returns? Being smarter can only help when it comes to solving difficult outstanding problems.

Again here is the famous SMPY study that shows no diminishing returns of achievement:

“Whether we like it or not, these people really do control our society,” says Jonathan Wai, a psychologist at the Duke University Talent Identification Program in Durham, North Carolina, which collaborates with the Hopkins centre. Wai combined data from 11 prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies2, including SMPY, to demonstrate the correlation between early cognitive ability and adult achievement. “The kids who test in the top 1% tend to become our eminent scientists and academics, our Fortune 500 CEOs and federal judges, senators and billionaires,” he says.

Is IQ everything? No. It’s not like you need to be a genius to find a spouse, to enjoy a TV show or movie, or to have a ‘good’ life, however that is defined. But in America in particular–except for perhaps lotto winners or luck-dependent professions (e.g. entertainers or podcasters)–IQ plays a non-trivial role in the aggregate at predicting one’s station in life (e.g. SES-status, career success, etc.). I think it’s better to at least accept this than to pretend otherwise–and not just at the low-end of IQ but also at the tails of IQ too–than to keep spinning this unconvincing narrative that IQ does not matter when the data shows it does.

Such honesty can open the door for more effective solutions for long-standing problems such as poverty or poor academic performance by accepting that the root cause is not always volitional (e.g. people choosing to be lazy), but something more immutable like biology. Instead of pouring billions of dollars of taxpayer money into trying to raise national reading scores by a tenth of a percent, maybe concede that some kids are not cut out or ‘wired’ for it, and that is perfectly fine–just like not everyone can be a D-1 football player. People have different strengths and weaknesses, yet American society is set up, especially early in life, on the implicit assumption academic skills are easily or readily attainable for all–for some yes, for many, no.

To use myself as an example, I have never been good at running. Even after losing a lot of weight (getting to a 22 bmi), I still found it hard (as do many others) . I would get out breath fast and feel the sensation of my legs turning into rubber or bricks. It’s just not in the cards. I didn’t get those genes that makes running easy or pleasurable. Fortunately, there are other things I can do for fun or exercise, like take a walk, hit the weights, or read a book–no problem. Now imagine a society in which running ability plays major role in one’s overall success at life, and not just hobby. I’d be at a disadvantage, and one that is not so easy to rectify. Just telling me to run harder or practice more would seem cruel or dismissive.

I also think it’s a sort of revealed vs stated preferences issue. The stated preference confers more status, so it’s voiced, compared to the uncouth concealed true preference. How many of the same public intellectuals who say IQ does not matter would in private refuse the opportunity to endow their children or themselves with more of this quality that allegedly does not matter or doesn’t exist? Why do so many of the wealthy preach equality or egalitarianism, yet send their kids to private schools, or spend untold tens of thousands of dollars or more on coaching (such as for admissions to elite schools) or other enrichment? The fact so many people talk about IQ and care about it (especially parents) despite the insistence by a vocal elite of its purported useless, is evidence it does mean something.