Charles Murray and Steve Sailer discuss how to make the SATs ‘tiger mom proof’:

More precisely, it rewarded systematic test prep, period, and it turns out that the people who work the hardest on test prep are Asian students and the white children of the affluent who want to get into elite schools.

Want to know what the hardest-to-prep-for kind of question… https://t.co/jy0XritGkN

— Charles Murray (@charlesmurray) February 23, 2024

As some people note on Twitter, how is it necessarily a bad thing that applicants who practice more also score higher. If the SATs are supposed to measure or predict college preparedness, a high-conscientiousness applicant who studies a lot and scores well would likely be better-prepared compared to someone who does less studying and scores lower even if equally intelligent. Or, a willingness and determination to get the highest possible score likely also predicts academic success and career success.

Murray proposes returning the notoriously hard analogies section as a solution, as those are supposed to be prep-proof. Interestingly, the ability to memorize long vocabulary lists would also be correlated with IQ. [0] So designing questions from a huge pool of vocab words would not help if sufficiently determined, high-IQ applicants memorize the word list.

Reading passage comprehension would be harder to coach, as processing speed, which is related to fluid intelligence, cannot be improved with practice, unlike word lists which can be memorized. Or the introduction of logic questions, like on the LSAT, which is known for having a high ceiling, and top scores (>170) are uncommon despite the widespread prevalence of coaching and apps.

Math competitions are one way for applicants to stand out, and are more resistant to ‘tiger moms’ owing to the difficulty and high intellectual ceiling of such competitions. Math competitions are today’s answer to the SATs becoming easier and having a lower ceiling, comparted to the pre-1995 SATs re-norming.

Same for the rise of GitHub and DIY-coding. In the pre-2000s, internet access and computers were more expensive compared to today, but nowadays anyone can set up repos with a smartphone. Coding tutorials are freely available online, as well as help forums like Stack Overflow, instead of having to pay for expensive books. This again levels the playing field and raises the ceiling at the same time.

But the crux of the problem is as follows: The returns to elite education have surged over the past 20 years, such as big salaries and prestige, all while the number of slots has stayed the same. This creates an arms race to game the system, which in the past wasn’t as bad, as there were enough slots for everyone with a decent score. Maybe you only needed a top 10% SAT score to get into a top-20 school 20+ years ago, compared to a top 1-5% score today.

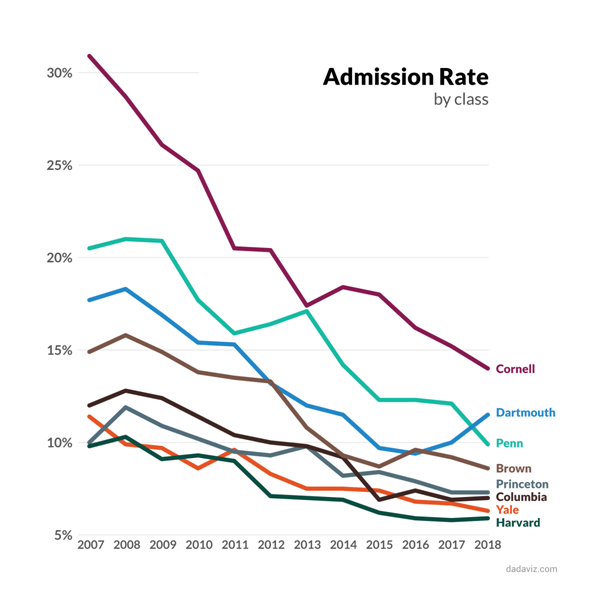

Consequently, admissions rates for top colleges have plunged over the past 15 years:

Shockingly! Among the top schools we looked at, the average admissions rate was 35.9% in 2006. By 2018, the admissions rate had plummeted to 22.6% (a drop of 37%). Not only that, but the more competitive the school, the harder it is to get into.

Given that demand exceeds supply by even the most qualified of applicants, if the objective is to prioritize one type of applicant over another, there is no answer that not involve some degree of favoritism or discrimination. If Murray wants poor, high-IQ whites to not be surpassed by high-SES, high-IQ Asians who are coached and practice tirelessly, this necessitates having to assign some sort of handicap to the latter or favoritism to the former.

Or in other words, they are reinventing affirmative action or rediscovering the justification for it. Instead of making a test that has such a high ceiling as to be impervious to coaching by rich parents, which is impractical or impossible, why not give a boost to low-SES applicants, or designate slots for low-SES groups. [I oppose affirmative action, and a test that is susceptible to coaching is preferrable to handicapping or favoring certain groups.]

Also, studies show that coaching only improves SAT scores by a little–a few dozen points on average–which although can tip the scales at the margins, is well-short of the hundreds of points promised by many coaching companies.

A 2010 study led by Ohio State’s Claudia Buchmann and based on the National Education Longitudinal Study found that the use of books, videos, and computer software offers no boost whatsoever, while a private test prep course adds 30 points to your score on average, and the use of a private tutor adds 37.

Overall, I posit it’s not wealth or tiger parenting that gives Asians an advantage, but more to do with a combination of high IQ and studiousness. Teens of all family income levels spend hours on social media, or playing video/computer games, or using Netflix. It’s not like insufficient time or inadequate access to resources is an issue. Anyone with a smartphone, which is about 100% of the population, can practice SAT questions.

[0] Murray writes:

Want to know what the hardest-to-prep-for kind of question is? Analogies. Vocabulary is a close second. Yes, you can try to memorize vocabulary lists, but the real edge goes to young people who reflexively try to figure out what an unfamiliar word means when they encounter one. It’s a strong signal of…you guessed it…cognitive ability. The College Board dropped both analogies and vocabulary.

I disagree about inferring the meaning. If the test is well-designed, inferring the meaning is hard, if not impossible. Like the word “adumbrate”. Either you know it or don’t. Or the infamous “regatta” example, which was used as an example of test bias. In either case, there is no evident Latin or other suffix or prefix to try to infer the meaning. The English language has some weird counterintuitive quirks. For example, proscribe means the opposite of what it should mean as suggested by the prefix ‘pro’, such as to proceed. Same for invaluable being valuable, yet invalid means ‘not valid’. Or how condone is easily confused for condemn but has the opposite meaning. Same for gainsay, which is to ‘deny, dispute, or contradict’, yet the prefix ‘gain’ suggests otherwise. Or enjoin, which has opposite but valid definitions: in the context of law, to prohibit or to issue an injunction, but otherwise to urge.