This article is going viral: Just own the damn robots

In Kurt Vonnegut’s 1952 novel, Player Piano, we are introduced to a future in which only engineers and managers have gainful employment and meaningful lives. If you’re not one of the engineers and managers, then you’re in the army of nameless people fixing roads and bridges. You live in Homestead, far from the machines that do everything, and are treated throughout your life like a helpless baby. The world no longer has a use for you. Anything you can do a machine can do better, and you are reminded of this all day, every day by society and the single omnipotent industrial corporation that oversees it all.

He wrote this 65 years ago. It couldn’t have been more apropos to what we’re witnessing now than if had he written it this morning, right down to the nostalgia-selling demagogue who seizes the opportunity to foment rebellion amongst the displaced and disgruntled. When millions of people start seeing their purpose begin to erode and their dignity being stolen from them, the idea that there’s nothing left to lose starts to creep in.

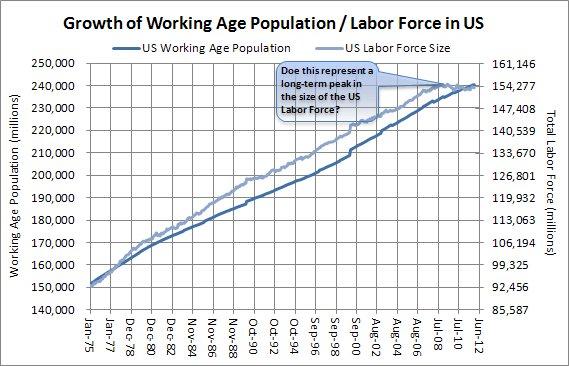

But the fact he wrote this 65 years ago, yet the labor force and population have grown in lockstep, augers against this:

Concerns about automation date back to the industrial age. Although ‘luddism’ is commonly used in the context of contemporary fears over technology and automation, the term originates from the early 1800’s:

The Luddites were a group of English textile workers and weavers in the 19th century who destroyed weaving machinery as a form of protest. The group was protesting the use of machinery in a “fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labour practices.[1] Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste as machines would replace their role in the industry.[2] It is a misconception that the Luddites protested against the machinery itself in an attempt to halt progress of technology. However, the term has come to mean one opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation or new technologies in general.[3] The Luddite movement began in Nottingham and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816. Mill owners took to shooting protesters and eventually the movement was suppressed with military force.

As shown in the post Evidence America is not (yet) dumbing-down, the notion that America is ‘dumbing-down’ long pre-dates the current era; Kurt Vonnegut wrote about it in 1961. Just as every generation thinks their generation is the dumbest [Jonathan Swift’s satires predate Vonnegut’s by 200 years], probably every generation thinks that their generation will be the one that finally eliminates all the jobs. In one’s mind, phenomenologically, these issues and observations feel acute and unique, but they have always existed.

There’s a great joke about an automated car plant in Japan, where the machines work in the dark (no need for light, they don’t have eyes) and there are only two living things authorized to be on the factory floor – a man and a dog.

What’s the man there for?

His job is to feed the dog.

What’s the dog for?

The dog keeps the man from touching any of the machines.

But why would companies, especially in an economic environment that is so competitive, keep employees that serve no purpose.

The only way out? Invest in your own destruction. In this context, the FANG stocks are not a gimmick or a fad, they’re a f***ing life raft. Market commentators rhetorically ask aloud what multiple should investors pay to own the technology giants. That’s the wrong question when people feel like they’re drowning.

I agree that buying and holding shares of Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft ,which are are not only leading this techno revolution but profiting immensely from it, is one the best ways to capitalize on this trend, which is what I have been doing for the past few years (along with owning Bitcoin).

I disagree, however, that automation will mean the ‘end of jobs’. It’s not that robots will take all the jobs, but rather the labor market will become increasingly bifurcated, with a ‘creative class’ at the top and the low-income service sector jobs at the bottom, without much in between. There is significant demand for service sectors jobs, of all skill levels, including skilled technical jobs such as coding, teaching, consulting, and engineering. But also huge demand for hospitality jobs. However, many of these jobs may not pay as much as the jobs they replaced, or bring much personal fulfillment.