From Yahoo (republished from Bloomberg), US Interest Burden Hits 28-Year High, Escalating Political Risk:

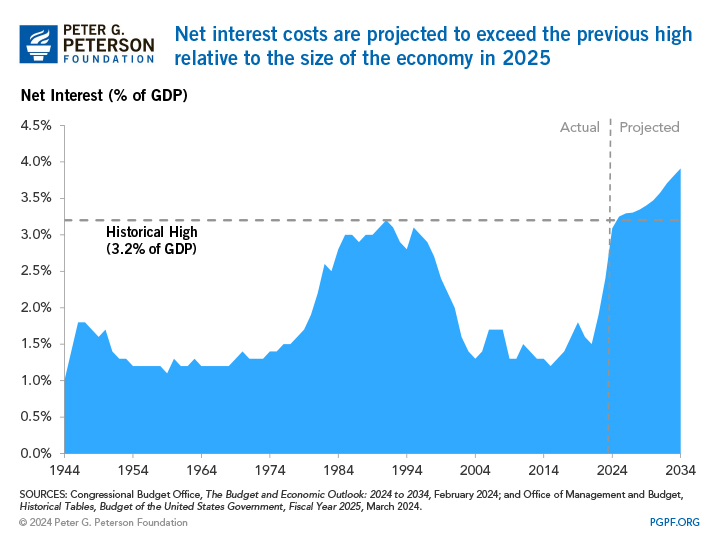

The Treasury spent $882 billion on net interest payments in the fiscal year through September — an average of roughly $2.4 billion a day, according to data the department released Friday. The cost was the equivalent of 3.06% as a share of gross domestic product, the highest ratio since 1996.

Historically high budget deficits, which caused total debt outstanding to soar in recent years, are a key reason for the increase. Those deficits reflect a steady rise in spending on Social Security and Medicare, as well as the extraordinary spending the US unleashed to battle Covid and constraints on revenue from sweeping 2017 tax cuts. Another big driver: the inflation-driven surge in interest rates.

Here is what it looks like. Relative to the size of the debt or GDP, interest has increased to near-historic highs:

Admittedly, it does not look good. Yet for something that is often described in alarmist language by the media, politicians do not seem to care, making promises to do something in some unspecified future but never getting around to it. Trump’s tax proposals will only expand the debt. So either this the ‘big short’ of a lifetime, or things will keep humming along as they always have, but with much more debt and a disinclination to do anything about it. I am more inclined to think the latter.

As investor here is why I am not concerned:

1. Pundits have made these doom and gloom forecasts about the debt forever. There are headlines from decades ago warning of a debt crisis. Given their terrible track records at this sort of stuff, it’s hard to take the media seriously. The financial media prioritizes clicks and page views over accuracy in reporting. An alarmist headline about a debt crisis succeeds at that objective compared to a more nuanced one.

2. As the U.S. economy keeps growing, each successive trillion dollars of debt or interest paid on debt becomes smaller relatively speaking.

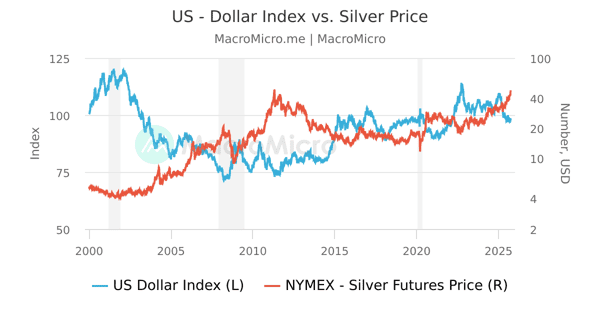

3. The US, being that it’s so economically dominant, has a lot of leverage in so far as negotiating its debt owned by its weaker creditors, such as Japan and China. This is the opposite of how debt usually works for individuals or nations historically, in which the creditor has power to inflict various punishments such as repossession. Or the debtor’s currency is devalued, like Germany during the ’20s. Yet the US dollar index has held up well over the past 20 years:

The dominance of the U.S .economy and the dependency of creditor nations on trade, increases America’s negotiating power and leverage overall.

4. The 1980s-90s saw a period of strong economic growth despite rising debt relative to GDP. Treasury bonds also did well. Anyone who bet against the stock market in expectation of a debt crisis lost money. Same for 2008-2024. The U.S. only solidified its global dominance during this period despite rising national debt.

5. Stocks can post substantial real returns despite large deficits. From 2008-2020 the S&P 500 and Nasdaq have consistently posted real returns in excess of 15-25% annually. From 2020-2024, again, the market has outperformed cash. Sitting on the sidelines for fear of a debt crisis only means becoming poorer in real terms and making yourself worse-off.

6. Unlike other countries, deficit spending does not make Americans poorer nominally speaking. Although inflation may reduce purchasing power if wages fail to keep up, because global wealth tends to be indexed in dollars, currency decline owing to deficits does not make Americans poorer in the sense of losing net worth. For example, if the Yen falls 3% relative to the dollar, Japanese citizens become 3% poorer as measured by global GDP guides (typically GDP and per-capita GDP are indexed to dollars when assessing if a country is growing or becoming wealthier or poorer), but conversely the dollar falling 3% relative to the Yen does not make Americans 3% poorer. However, it would make travel more expensive, but this is not as concern for the vast majority of Americans.

7. Firms are more nimble compared to central banks. Corporations can adjust to inflation by raising prices, so profits rise accordingly, as do wages. (Whether wages lag inflation or precede inflation is debated.) This why stocks are a good hedge, due to the ability of firms to adjust prices instantly. The problem with cash is it tends to have the most lag in this shifting process. By the time the fed gets around to raising rates, much of inflation will have already occurred. There was an over 2-year lag between ~0% interest rates in late 2021 to interest rates finally catching up with inflation, by early 2024. Thus, cash tends to have a negative real yield even when there is high inflation.

8. Inflation hedges are unreliable and have high opportunity costs. Let’s assume you believe the debt situation is a crisis or will soon be a crisis, then what? Gold will not necessarily be the answer. Gold failed to hedge in 2021-2023 as inflation surged and the fed raised interest rates, only to rally in 2024 after the fed began to cut rates and inflation subsided–the exact opposite which everyone was expecting, or predicted by the ‘gold is an inflation hedge’ narrative.

Treasury bills or cash can also work as a hedge, but you run into the problem of the fed suddenly cutting interest rates, like during the early ’90s, 2001-2003, or from 2019-2020. This will cause the coupons on subsequent bills to shrink rapidly, and at the same time assets such as stocks and real estate will surge. So you miss out on all of that, and you’re stuck with bonds that may have a negative real yield. Or cash that does nothing, and at the same time everything is 20-40% more expensive.

As it’s said, no one rings a bell at the bottom when it’s time to reenter the stock market. Sitting on the sidelines not uncommonly means having to scramble to buy back in at a much higher price as the awaited pullback never comes. In economics, this is what is called an opportunity cost; how much upside are you willing to forfeit to wait for an event which may not happen? Ask people who postponed buying a home from 2010-2020 how well that worked out.

9. The stock market is not the economy. This is the conundrum when it comes to ‘the economy’ vs. ‘the stock market’. Profits and earnings are the only things that matter when it comes to stocks (and to a lesser extent, tax policy), whereas the state or health U.S. economy has many more variables, such as GDP, labor market, population growth, productivity, debt, inflation, and so on. The stock market, being that it’s composed of firms, is correlated but not the same as the economy, as I explain in the article Why Declining Population Growth and Sluggish GDP Growth are Not a Concern for Investors.

As an investor, you’re investing in companies, not GDP, and although to some extent are correlated, differ in crucial ways. [Prediction markets, however, can allow for people to speculate on such economic metrics as GDP or inflation in isolation.] Public companies must return profits to shareholders, whether in the form of dividends, buybacks, or retained shareholder equity. So a public company with 20% profit margins, in theory, can yield a 15% real return for investors long-term vs. 5% inflation or 5% GDP growth. This explains how the stock market can still post strong real returns for investors despite a lot of things seemingly being wrong with the economy or society.