Marc Andreessen’s article Why AI Will Save The World went hugely viral. As to be expected, the tone is breathlessly optimistic. I agree that AI-doom fears are likely overblown and unfounded. The people who are championing this view have shifted the burden of proof to everyone else to prove why AI will not destroy the world, but this is not a persuasive argument that it will.

In terms of economics, he argues that AI will not destroy jobs, invoking the lump of labor fallacy, which I also agree. Technology’s track record of destroying jobs is surprisingly poor despite all the hype and alarmist language the issue gets. Even to this day, horse and buggies still operate in many cities. But I disagree that AI will make things cheaper. He writes:

That last point is key. Would Elon be even richer if he only sold cars to rich people today? No. Would he be even richer than that if he only made cars for himself? Of course not. No, he maximizes his own profit by selling to the largest possible market, the world.

The Lump Of Labor Fallacy flows naturally from naive intuition, but naive intuition here is wrong. When technology is applied to production, we get productivity growth – an increase in output generated by a reduction in inputs. The result is lower prices for goods and services. As prices for goods and services fall, we pay less for them, meaning that we now have extra spending power with which to buy other things. This increases demand in the economy, which drives the creation of new production – including new products and new industries – which then creates new jobs for the people who were replaced by machines in prior jobs. The result is a larger economy with higher material prosperity, more industries, more products, and more jobs.

Do you think large companies are going to take it lying down as technology erodes their profits? Heck no. They didn’t the past century despite an abundance of new technology, and they won’t let AI do it either. They are going to adapt with the times. Indeed, corporate profits are the highest they have ever been in spite of more technology than ever. The idea that technology is going to make everything cheaper is unfounded. It may make certain things cheaper, but this will be offset by hidden costs.

There are many ways companies adapt, as well as economic forces that keep prices high despite automation , including but not limited to:

1. Planned obsolescence (stuff breaks more often, by design or to save manufacturing costs). If a computer only lasts half as long (either due to breaking or becoming obsolete) despite costing half as much, it’s effectively the same price. I have observed this trend myself. My newest laptop had a major keyboard failure after a few years, but my older laptops last forever and still work mostly well.

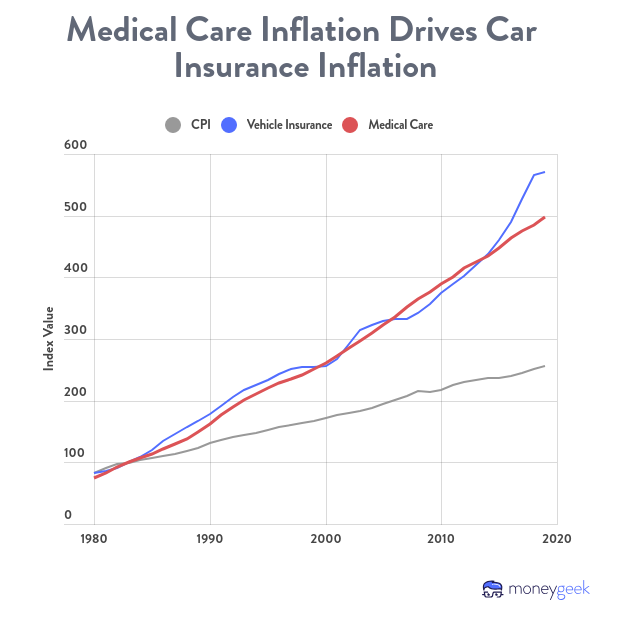

2. Recurring services (so-called ‘everything-as-a-service’). I think this is a major one and overlooked by experts. People are spending so much on services overall, like Netflix subscriptions, Substack subscriptions, podcast subscriptions (like Spotify), subscriptions for apps, games, etc. It all adds up to a lot of money. Companies realized they can make more money by charging less upfront and then making it up later by making their product a service. Cable, phone plans, software (especially cloud apps), and internet are more expensive than ever even if PCs are cheap. So many things are recurring , with expensive lock-in plans and high cancellation fees. Same for insurance, which is more expensive than ever and recurring. For example, healthcare and vehicle insurance has exceeded inflation (so much for technology making things cheaper):

3. Veblen goods/luxury goods, sticky prices. Some goods remain expensive even if profits can be realized by selling them cheaper–so called Veblen goods. An obvious example are Rolexes. There are many instances of hardware not becoming cheaper, such as iPhones. The first generation iPhone from 2007 costs about the same as the latest iPhones, adjusted for inflation. $1,000 seems to be a sticky price for new iPhones. Private jets also haven’t gotten cheaper despite aviation technology improving considerably over past fifty or so years. Cars still cost a lot despite over the past century the process of manufacturing cars becoming much more automated at scale. It’s likely that TVs and PCs are just exceptions of major price deflation, not the norm or to be expected.

4. Shrinkflation, enshitification (which is related to #1). This means you either get less than you expect, or worse quality. A worse user experience, more ads, and more personal user information harvested for ad-optimization purposes, is the price you pay for cheaper or free services. Same for more paywalls, more annoying sign-up prompts, throttling, etc. Or more bloatware.

Of course, quality may improve (the latest iPhone objectively is better compared to a 2007 iPhone), but this is not the same as things becoming cheaper. Healthcare is still expensive even if treatments have gotten better.

5. The Baumol effect. Labor is a major and persistent cost despite automation, such as doctors, nurses, plumbers, musicians, etc. which are jobs that are hard to automate. Sure, an AI doctor can diagnose you, but good luck having it do surgery. This funny and astute tweet sums it up:

A doctor does a lot more than diagnose, and not every diagnosis can be made remotely, such as colonoscopies, MRIs, or electrocardiography.

6. Finally, the difficulty of automating menial jobs, like cleaning engines, washing floors, flipping burgers, etc. This is related to #5. Such jobs are hard to automate due to high overhead costs and the inherent difficulty of automating the fine motor control of the human arm and hand. Even if a robot can do those jobs better than a human, companies cannot afford to replace all their human workers with robots, at least not yet at scale given how much robots cost. It would cost too much, and even then humans would still have to maintain and supervise the robots.

Overall, AI will make some jobs or services cheaper with minimal hidden costs, such as writing those boring, tedious high school or college essays that everyone dreads having to do, and teachers hate having to grade. I think paper mills are at greatest risk of being automated. If you need a passable, c-grade essay on Shakespeare, maybe AI can do that cheaper than having to hire someone to write it. But I don’t see it suddenly ushering in an era of post-scarcity or everything being cheap.

I remember what happened to drafting as a career. Decades ago, an engineering firm, of architecture firm would have several draftsman to work on drawings for the engineers or architects. Then CAD computer assisted drafting came along. I was trained as a draftsmen so I remember this time. A firm might have say, 6 draftsmen, then CAD came in, they didn’t need 6 draftsmen, so 3 were let go, the the engineers realized they had CAD on their computer too, they could just do it themselves. Then the rest of the draftsmen were let go. A whole avocation for many people is now mostly gone. I expect AI is going to do this for many office jobs too. Offices used to have many secretaries typing away, now, Microsoft word and computers, have reduced this to 1 or 2 in a lot of offices. So yes, technology can change employment a great deal. Jobs that are more physical in nature, except for trades often don’t pay as well.

What about legality?

If the AI diagnoses you INCORRECTLY, will the software company be sued? If the treating clinician is still deemed responsible, what is the incentive to use it to be the final decision makers?

Seems AI replaces/reduces assistants/helping staff: draftsman, secretaries, maybe medical assistants, but not the final decision makers such as engineers, doctors, lawyers, etc.

Same for trades where electricians and plumbers are the final decision makers as well