From Erik Hoel, “John von Neumann Shot Lightning From His Arse.”

It’s more like the author is shooting from his own arse. The author engages in a sort of goalpost moving, whereby arguing that because some of the feats attributed to von Neumann are false or exaggerated, that somehow this is incontrovertible proof that his success was due to tutoring, or not that special or unique.

He begins with a misconstruction of the pro-hereditarian side:

Pop-hereditarians scoff at the very idea that Nurture’s contribution might be non-zero, fanatically dismissing that even the best education—gasp—could have an effect. Given an inch, they’ve taken a mile, and become annoyingly identical to the blank slatists they once criticized.

No one on the hereditarian-side has ever dismissed environment altogether. This is a straw man on the author’s part. Rather, nature is more important or of greater explanatory power compared nurture, not that they are incompatible.

If anything, the ‘blank slatists’ have a much bigger megaphone in the media and presence in academia compared to the hereditarian-side. This was seen during the controversy following Charles Murray’s 1995 book The Bell Curve, co-authored with Richard J. Herrnstein, in which supporters of the book were overwhelmingly outnumbered by critics, even though the empirical evidence was sound. The nature-side of the debate has been so thoroughly browbeaten to submission, save for some dissenting voices online, because it’s literally unsafe to discuss these views otherwise.

For example, in 2017 when Charles Murray was invited to speak at Middlebury College, protesters physically tried to prevent him from entering the building. Injuries were reported. Property was damaged. To say that they have ‘become annoyingly identical’ betrays any objective reporting of the situation.

When it comes to the Nature vs. Nurture debate, the truth is in the middle. It will always be in the middle. Yet middles are unsatisfying.

This is an example of the middle fallacy, or more specifically the argument to moderation, which assumes that the truth must lie between two opposing positions. But the truth is often more granular. The purpose of science is to investigate phenomena by gathering and evaluating evidence, not by splitting the difference between viewpoints. What would be the point of even debating this if the answer is just assumed to be “50/50”?

About tutoring:

In this milieu of turn-of-the-century Budapest Johnny was aristocratically tutored by a “tribe” of tutors and governesses at his 18-room top-floor downtown home until he turned 10. After that, he went to one of those “world’s best high schools.” There, he was taken under the wing of Laszlo Ratz, who was described by Eugene Wigner (winner of the Nobel Prize, who was a year ahead of Johnny under Rátz and one of Johnny’s best friends) as one of the greatest math teachers of all time.

But ‘aristocratic tutoring’ was fairly common back then, yet the vast majority of wealthy Hungarian youths tutorted in this manner turned out no where near as brilliant or as eminent as von Neumann, similar to how so few wealthy tutored English youths turned out as brilliant as John Stuart Mill. This is is just misdirection on the author’s part; tutoring does not change the evidence that innate ability likely explains how von Neumann was head and shoulders above his ‘Martian’ peers, who were also tutored in a similar manner.

Fast-forward to today, the same is seen with high-stakes math competitions: thousands of high schoolers practice and are tutored, but only the smartest win and advance to higher levels of competition. Or the LSAT: many practice and use expensive apps, but 175-180 scores are still rare and difficult. With the environment more or less controlled for–that begin practice and coaching–innate ability shines through. There is no getting around this. Or pro sports: millions of kids practice sports, and many even have private coaches or attend expensive private schools that specialize in sports–yet few make it pro. Wealthy parents, especially in New York City, collectively spend millions of dollars for enrichment programs and coaching in the hope that their dull children will be admitted to selective schools.

The author again downplays von Neumann’s supposed brilliance as being the product of education, being at the ‘right place at the right time’, and connections:

But even in his incredible output and the legends around him, Johnny’s overall academic oeuvre seems closer to what one would expect from someone whose talents were due to his perfect education vs. his supposedly-superhuman brain itself. His work is a triumph of formalizing things beautifully and quickly, being in the right rooms, flat-out knowing more than other people, and competitively beating them to the punch (he described himself in a letter to his daughter as “an ambitious bastard”).

But when von Neumann was among other exceptionally smart and well-educated people, he still stood out–something attested to by Bethe, Teller, Einstein, among others. Those contemporaries also had connections and happened to be in the ‘right place at the right time’; otherwise they wouldn’t have been together in the first place. So it doesn’t make sense to attribute von Neumann’s success merely to connections when everyone around him shared the same historical circumstances.

He says, “…flat-out knowing more than other people, and competitively beating them to the punch.” But that’s literally what being smarter entails. Smarter people know more and can reach correct solutions faster than others. This is supposed to be a ‘dunk’, but it’s more of a ‘own goal‘ on the author’s part.

I can attest to this, such as being the first to come up with the idea of shorting Bitcoin to hedge the stock market (I profited big this week doing this) despite not having any finance or Wall Street background. Or math research: I developed five analytical techniques that when combined yielded new identities of a certain special function, closing a 28-year gap between my result and the penultimate one. No math background either…just reading and picking it up.

Von Neumann’s brilliance was on display during the Manhattan Project, where he proved that a fission bomb would be safe, instead of igniting the atmosphere in an uncontrollable chain reaction as feared by Teller, who was not as smart and had miscalculated. This effectively saved the Manhattan Project. He also co-developed and championed the concept of ‘explosive lenses‘ to achieve a more uniform implosion for the fission bomb, without which it would not have detonated correctly:

When it turned out that there would not be enough uranium-235 to make more than one bomb, the implosive lens project was greatly expanded and von Neumann’s idea was implemented. Implosion was the only method that could be used with the plutonium-239 that was available from the Hanford Site.[325]

He also provided invaluable calculations for the development of the much more powerful hydrogen bomb, harnessing the computational power of the EDVAC, an early supercomputer at the time. One can argue that others also played a key role, but von Neumann’s proposal of the explosive lens concept was his. Yes, as the author notes, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert also share credit for the development of the EDVAC, but I would argue that it was von Neumann who codified it with his report First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC, without which the technology would not have realized its full potential.

Yes, Laszlo Ratz in 1915 apparently also had the foresight to teach his students nuclear detonation devices and computer architecture. He was that good of a teacher. So when von Neumann joined the Manhattan Project in 1943 all he had to do was regurgitate what he had learned. I am joking of course, but the author puts way too much emphasis on tutoring or rote practice. Here we have a situation where von Neumann was placed in a new environment with totally new problems, such as nuclear weapons and computers, where he couldn’t have possibly memorized the information ahead of time, yet he still made breakthroughs.

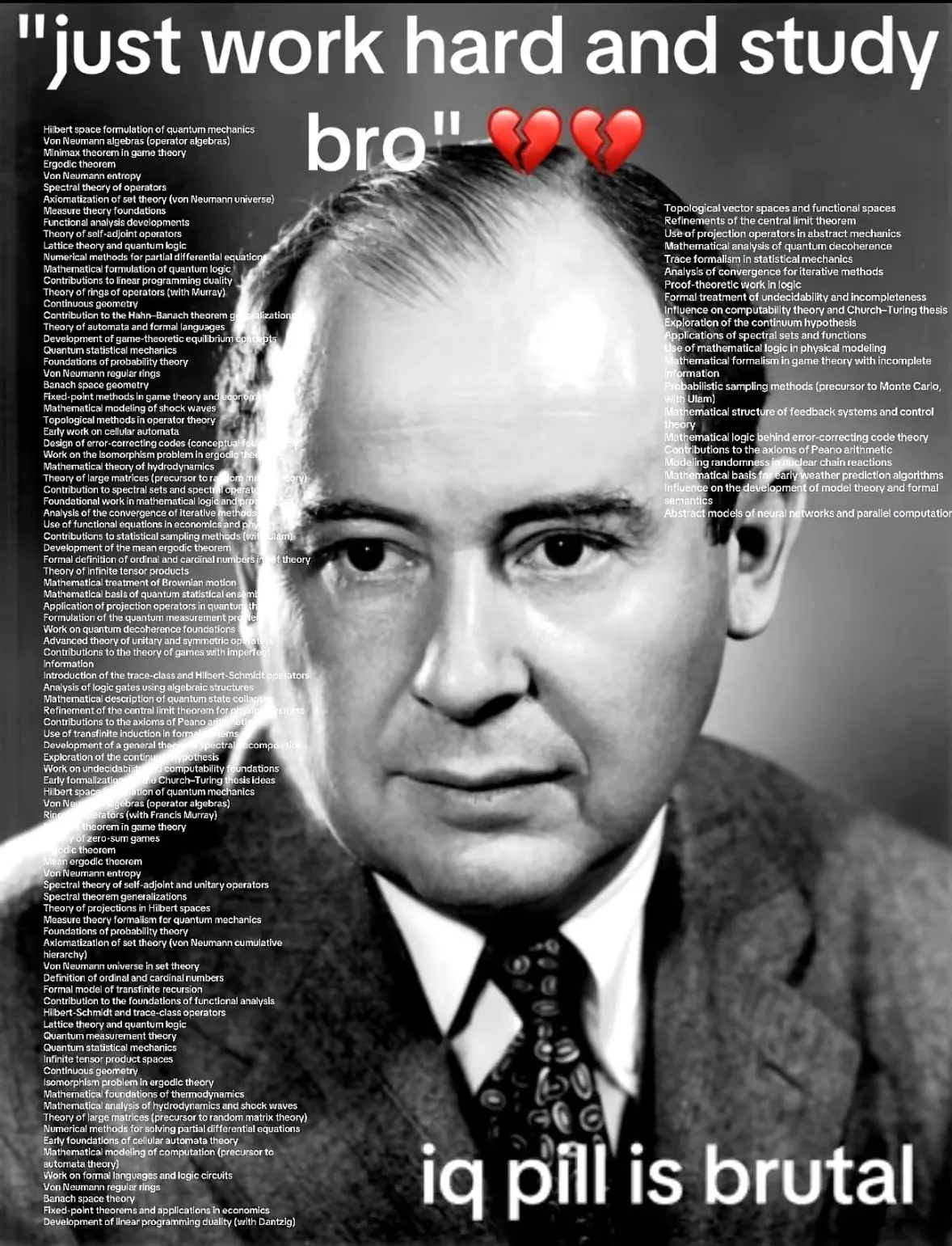

I don’t want to come off as beating up on the author, and I will concede some points to him. Consider the huge list of von Neumann’s accomplishments, which although visually formidable, many of these can be consolidated:

For my own paper, the five methods could be expounded in five separate papers, but I consolidated it into a single, longish paper. If I wanted I could take some of my other ideas and expound on those in separate papers too, for a total of maybe 10 short papers.

If today’s mathematicians and physicists seem less brilliant or less productive, part of the explanation may be that discovering new results and getting them published has become far more difficult than it was in von Neumann’s era. He had the advantage of being alive when publishing was faster and easier. Not only were papers much shorter, but peer review was much faster and acceptance rates were much higher.

Nowadays, papers are expected to adhere to higher standards of originality, rigor, and formatting. Peer review can easily take a year or longer from submission to publication. ArXiv was established in 1997 to share unpublished results, instead of having to wait for peer review to finish. It’s not uncommon for new PhDs in economics, mathematics, or physics to have no sole-authored original research. Even when their dissertations are up to par, the work may still fall short of being publishable.

And I don’t want to dismiss tutoring altogether. I was tutored after I had exhausted the normal school math curriculum, and I would be lying if I said it did not help me, but I am under no illusion that what separates me from someone like, say, Grigori Perelman is ‘more tutoring’ or ‘better tutoring.’ That is just raw talent on his part. Which is fine. Let’s at least be honest about it than create false narratives. Like trying to split the difference between a falsehood and the truth, this does a disservice to everyone even if it feels good.

To bring this back, it’s hard to overstate von Neumann’s importance during the first half of the 20th century in terms of influencing the second half. I would argue, more so than any other individual, he created or laid the groundwork for the social order we see today. The creation of the fission bomb swiftly ended the Second World War, leading to a new world order, with the US on top. The development of fusion bombs arguably saw the end of world wars. This allowed for economic flourishing and increased trade. Such prosperity and peace also hastened the decline or reform of Communism, like as seen in Russia and China. The advent of computers also made America a technological superpower and the envy of the world.

But overall, the fact some of von Neumann’s alleged accomplishments or feats, such as having a photographic memory, may not hold up to scrutiny or are somewhat exaggerated by his biographers or folklore, does not change the fact he was also smarter than many of his peers who had a similar upbringing as his.