It’s been almost 3 years since so-called ‘generative AI’ broke into the public conscious. Commercial products that harness this technology such as Chat GPT, Grok, Gemini, Cursor and Claude have seen widespread adoption. There is no denying at this point that these tools are mainstream. What is much more debatable are the economic implications of AI. For example, will AI will engender a tailwind to economic productivity, or will the impact of these technologies prove to be much more limited or local in scope.

The Solow Paradox, named after the late Nobel-Prize-winning economist Robert Solow, describes the disconnect between technological progress and productivity, or in his own words, “You see computers everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” There is all this amazing technology, yet it’s not moving the needle much where it should, such as productivity. Tyler Cowen famously coined the phrase ‘the great stagnation’ to describe how productivity growth has slowed:

If history is any guide, AI will meet the same fate as personal computers and the World Wide Web of failing to boost productivity as anticipated or hoped. Why? There are many possible explanations, but I blame “time sinks”. The need for companies to maximize profits comes with the cost of reducing productivity–by making said services less useful for end-users than they could otherwise be. This means time is wasted on superfluous features, rate-limitations, restrictions and so on, instead of harnessing the full economic potential of such technologies.

Without fail, a cool web-based technology or service eventually becomes severely degraded to the point of not being useful, or only a shadow of its potential. After capturing critical market share, the users are monetized heavily and or heavy restrictions are put on usage, starting the degradation phase. So my advice is, if you see a cool and seemingly underpriced web service, try to get the most out of it while it is not degraded.

For example, for Chat GPT, a rate-limiting message:

Such time sinks are common online. The need to maximize ROI–but also to thwart ‘threat actors’ such as hackers, web scrapers, or spammers–means popular services are constantly throwing roadblocks to usability. In the ‘Web 1.0’ era this was pop-ups and slow internet speed. The latter was unavoidable owing to the limitations and cost of broadband, but there are new roadblocks, such as captchas, which have becomes even more pervasive, ironically, now made worse by AI.

For example, the all-pervasive Cloudflare captcha, a familiar sight:

The problem is when the captcha not uncommonly fails to load properly, such as on mobile devices or if the internet connection is slow, or it otherwise malfunctions, making the sought content inaccessible. If one captcha wasn’t bad enough, how about two, for added security:

But also, the disabling of existing features or the introduction of new, unnecessary features, so-called ‘feature bloat’, that hurts usability–ultimately wasting the end-user’s time. Cory Doctorow described a similar phenomenon–what he coined ‘enshitification’–to describe the worsening user experience and disregard for user privacy by avaricious big tech companies.

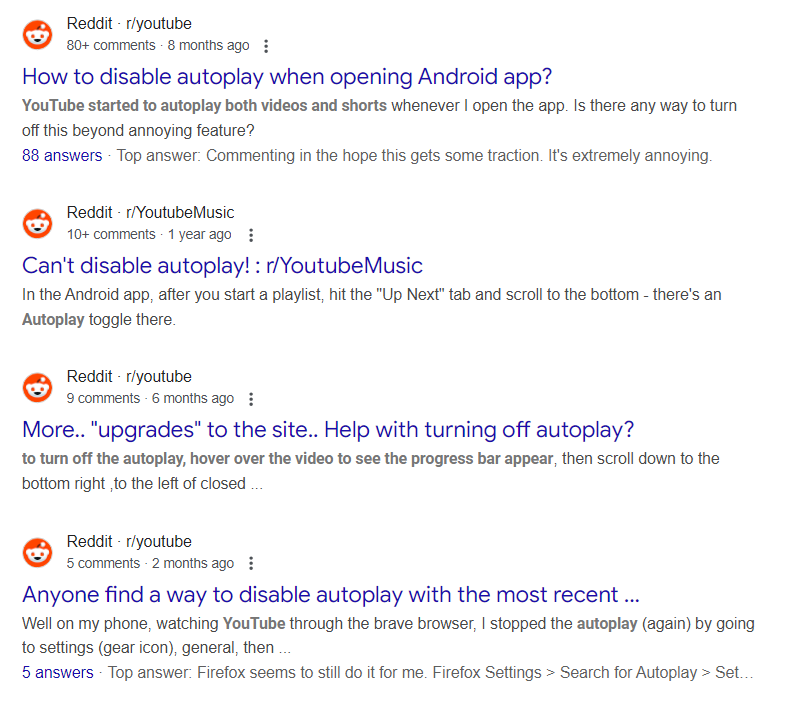

For example, YouTube quietly removed the ability to disable autoplay. The feature simply does not exist anymore:

Many users on Reddit report frustration of not being able to disable the auto-play:

Users were not consulted on this matter. Tech companies call it a “roll out”, meaning they will try it on some users, and then more depending on feedback. Here’s some feedback: It sucks. Alphabet, the parent company of YouTube, simply decided one day, “Nope, you can no longer disable videos in a playlist from automatically playing, sorry,” and that was that. Auto-play, of course, means more opportunities for Google to run YouTube ads rather than letting users be in control.

Or look how many ads are on YouTube now. It’s gotten out of control. Videos are often interrupted with ads every eight minutes or so, on top of sponsored content. Apparently there is an inexhaustible market for VPNs or Squarespace hosting. The incentives also favor longer videos to maximize potential ad revenue. For things such as tutorials, this means lots of filler, which wastes the viewer’s time. Of course, this is rational from Google’s perspective maximize its profit, and now YouTube is a $100+ billion behemoth in its own right (which in in hindsight made Google’s acquisition for only $1.65 billion a great investment), but there is no denying that this also in the process erases some of its usability.

Additionally, people collectively spend 11.5 billion hours/day on social media, which can also be thought of as a ‘time sink’ in its own right. Similar to time wasted ‘doom scrolling’ on social media, ‘AI slop’ may similarly hurt productivity, but in a different way. So much time will be wasted double-checking the correctness or authenticity of content, or separating ‘fact from fiction’. That lifelike video from your boss telling you to wire money somewhere–now you have to double-check with him just to be sure it’s not fake. And then triple-check just to be absolutely sure.

As for feature bloat, the once-slick Gmail has now become a bloated, slow-to-load “Google Workspace”. It’s so slow, there is even a progress bar. We’re not talking loading a cutting-edge video game or running GPU clusters for a life-like AI simulation, but trying to load email–a technology that even predates the personal computer. I don’t want a ‘workspace’. I want to check my *%&*ing email.

Signing up for websites is much more difficult and time-consuming as well. The once ubiquitous “username and password” has been replaced by either having to fill out long forms of personal information or phone verification (to thwart spammers). A common deceptive technique is to require the registrant’s email and phone number before throwing a paywall, so they already got your info. Or convoluted password requirements, such as having to use weird character combinations so the password cannot be cracked, even though such passwords may be worse for security by being impossible to remember, so people will write them down or store them on their computer in plaintext instead of ideally memorizing them.

By comparison, airplanes and other technologies have only seen improvements without such tradeoffs. Yes, seats are more cramped, but flying is safer than ever and still relatively fast. Cars are safer and more fuel efficient. Cars also have more features, but this hasn’t hurt their usefulness. TVs are bigger and better in every respect. Medical technology has gotten better too.

Also, those industries are much more competitive and such services are more interchangeable, compared to ‘moat effects’ and winner-take-all markets seen with large tech companies. A car company, fast-food joint, airline, or appliances manufacturer that attempts to extract too much value from users or sees too much degradation, is at risk of falling to competitors. If Ford cars are bad, you can always buy GM, or one of dozens of other brands which more or less provide adequate transportation, but there are far fewer, if any, decent alternatives to Apple, Google, or Facebook. There are only two smartphone app marketplaces: Apple’s App Store or Google Play Store.

This also makes tech companies such great investments, as they make so much money and are so dominant, but the roadblocks, degradation, and unwanted features are annoying at the same time. The need to make products highly profitable comes with a cost of some or most productivity. Hence–unless companies decide to either tolerate more bots or spam, or sacrifice some profits–I predict that any productivity gains attributable to AI will be negated by time sinks elsewhere.