Many people assume that the idea of having a fast or slow metabolism is just a myth, or that people are lying when they say they have a fast or slow metabolism. For example, a recent Reddit post “‘Fast metabolism’ is a lie, stop making yourself feel bad” went hugely viral, garnering 1829 votes and 288 comments, almost all in agreement.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but fast metabolisms are not a lie. As discussed in the posts “Individual differences of metabolism are real and matter” and “Slow metabolisms are not a myth“, to deny that fast or slow metabolisms exist or are a myth, is tantamount to denying that smart or dull people exist, that tall or short people exist, or any other trait in which humans vary, which are all of them.

And it’s not that metabolism only varies a little either between individuals; it varies surprisingly a lot. Two otherwise identical people can still differ in resting metabolic rate (RMR) by as much as 1,000–2,000 calories per day. That is a lot, or about as much inter-individual variance (when dividing the mean by the standard deviation) as something like IQ. Similar to IQ, there is no obvious explanation for why metabolism varies so much, although there is likely a genetic factor. Like trying to raise IQ, there is not much that can be done to raise metabolism (without also getting fatter in the process, such as by eating more, which I assume is not what people have in mind when the putative objective is weight loss).

So where is the hard evidence?

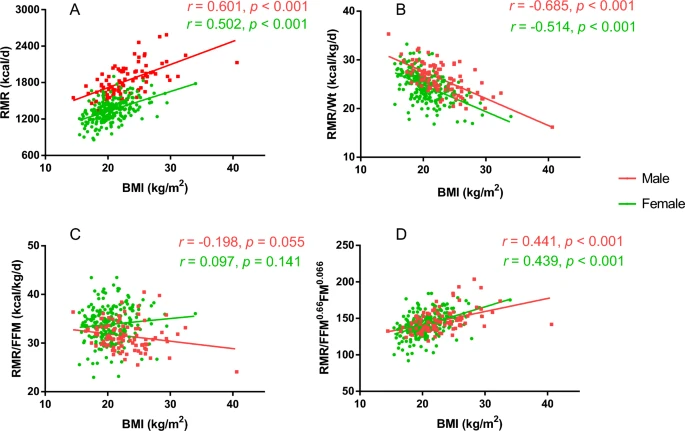

A 2024 study from China found “mean RMR for men and women was 1825.2 ± 248.8 and 1345.1 ± 178.7 kcal/day, respectively.” Dividing the standard deviation by the mean gives a ‘coefficient of variation’ of 1/7.3, which is comparable to IQ. Shown below, this represents enormous inter-individual variance of RMR when either adjusted for FFM (fat free mass) and relative to BMI (body mass index). Those at the top decile have as much as 1.7x as fast of a metabolism compared to those at the bottom decile when controlling for sex, BMI, and FFM. This is the exact opposite of the claim that “fast metabolisms are a lie”.

Some argue that IQ scores have little predictive value, or more formally, that they lack construct validity. But a 30 point (or 2 standard deviation) IQ difference, say 90 vs 120, is the difference between the cutoff for special ed vs gifted classes. Or the IQ of the average high school graduate (100) vs a typical math or physics doctorate (>130). Such differences are far from trivial when it comes to real-world outcomes.

Likewise, a 500 kcal difference between someone who is +1 vs -1 standard deviations of RMR is equivalent to 500 calories, or in practical terms, an entire meal. This is hardly insignificant, especially in the context of dieting, where every calorie counts, as I will explain later. The guy with the +1 standard deviation metabolism effectively has a ‘free meal’ compared to the guy with the -1 metabolism.

When it comes to height, the average man is 176 cm tall with a standard deviation of 7 cm, giving a coefficient of variation of just 1/25. In other words, metabolic rates vary about three times more between individuals than height does–yet height differences are so noticeable that they’ve even become the subject of memes. Or ask anyone who has tried using a dating app.

Again, it’s not known why otherwise physically identical people vary so much in metabolism. It could be due to differences of NEAT (non-activity exercise thermogenesis), which describes non-purposeful movement such as fidgeting, or the internal organs. Muscle only explains a small bit of it, as skeletal muscle burns few calories relative to the metabolically-hungry organs such as the heart, liver, and brain. What about physical activity? The study accounted for this by instructing the participants to abstain from vigorous activity leading up to the study:

Participants were instructed to visit the Sir Run Run Hospital (Jiangsu, China) following a minimum 10 h fasting period, during which they refrained from consuming any stimulant substances (e.g., caffeine, tobacco) for at least 4 h. Additionally, participants were required to abstain from engaging in vigorous physical activity for 24 h prior to their visit23. All measurements were performed between 8:00 and 10:30 in the morning.

Disappointingly, NEAT cannot be raised. The body distinguishes between spontaneous NEAT activities, like fidgeting, versus intentional movement, such as exercise. Because exercise is by definition purposeful, it doesn’t provide nearly the same metabolic boost as genuine NEAT.

A 2014 study, “Hypometabolizers: Characteristics of Obese Patients with Abnormally Low Resting Energy Expenditure,” examined 628 morbidly obese patients referred to a bariatric clinic. The researchers found that resting energy expenditure (REE) follows a normal distribution, with about 10% of participants showing REE values 25% lower than predicted by regression equations, as shown below. (For clarity, REE and RMR are used interchangeably, as both refer to the same physiological measure.) These individuals were classified as “hypometabolizers,” meaning they had an unusually slow metabolism. They also had a higher BMI.

There are many other studies with similar findings. It’s hard to find any study where obese people, in the aggregate, have abnormally fast metabolisms (controlling fat and lean body mass) compared to non-obese subjects.

Same for metabolic adaptation to dieting, the degree of which also follows a normal distribution. Some people really are ‘metabolically blessed’ in the sense of either resisting weight gain, losing weight faster, or keeping the weight off longer. Some individuals are deemed ‘diet resistant’, in that their bodies stubbornly hold on to the weight, instead of easily shedding the pounds on the opposite extreme of being ‘diet sensitive’.

From a 2002 study, “Decreased Mitochondrial Proton Leak and Reduced Expression of Uncoupling Protein 3 in Skeletal Muscle of Obese Diet-Resistant Women”:

The highest and lowest quintiles of weight loss were defined as diet responsive and diet resistant, respectively. After body weight had been stable for at least 10 weeks, 12 of 70 subjects from each group consented to muscle biopsy and blood sampling for determinations of proton leak, UCP mRNA expression, and genetic studies. Despite similar baseline weight and age, weight loss was 43% greater, mitochondrial proton leak-dependent (state 4) respiration was 51% higher (P = 0.0062), and expression of UCP3 mRNA abundance was 25% greater (P < 0.001) in diet-responsive than in diet-resistant subjects.

And from a 2021 study, “Metabolic adaptation characterizes short-term resistance to weight loss induced by a low-calorie diet in overweight/obese individuals,” the first paragraph acknowledges how much people vary despite adhering to the same protocol:

Although low-calorie diets (LCDs) (800–1400 kcal/d) can reduce weight by 8% over a 6-mo period (4, 5) there is notable response heterogeneity among cohorts. This weight loss response heterogeneity exists despite adherence and compliance to a weight loss diet (6). Characterizing the metabolic components of controlled weight loss success will be crucial in predicting the efficacy of weight loss interventions in obese populations and developing future personalized treatment plans.

This again suggests actual biological factors for individual response to dieting. “Increased mitochondrial proton leakage” is a fancy way of saying “more waste heat energy,” meaning the body is less efficient in people who lose weight faster. Such leakage means impaired ATP production, similar to the process by which DNP (2,4-dinitrophenol) works, minus the the overheating and occasional lethality.

The second study concludes:

Metabolic adaptation refers to reduced RMR compared with what is anticipated based on body composition (8, 9). ODR participants had a greater metabolic adaptation than ODS participants. In other words, the ODR group had greater reductions in actual RMR compared with what was expected based on FFM, age, and race. This difference existed despite both groups having comparable RMR throughout the LCD. Metabolic adaptation after long-term weight loss has been established (29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34). In the present study we have shown that metabolic adaptation exists over a short duration (28 d) in agreement with previous research (35) and more notably characterizes individuals who have a blunted response to weight loss.

Metabolic adaption is increased in subjects who are resistant to dieting (ODR) compared to participants sensitive to dieting (ODS). Even if the mechanism for this is not entirely known, it’s undeniable there is considerable variability that is of a biological origin, being that the environment has been controlled for.

Differences of metabolism have also been observed in animal studies, such as livestock. This is called “residual feed intake“, which measures how much feed an animal consumes compared to how much it’s predicted to consume for its weight or for a given yield (e.g. eggs, per pound of meat, etc.). This has been studied extensively since the concept was first conceived in 1963 by Robert M. Koch, with some studies having hundreds of citations. The implications are obvious: more metabolically efficient animals need less feed, meaning higher profit margins, so it makes sense to investigate this, especially at scale in the context of factory farming. Like variability of human metabolism, there is no smoking gun. It’s not like metabolically efficient or inefficient animals are in any way different in terms of activity level or health. Yet when it comes to differences of human metabolism, we’re led to believe such differences are illusory or only tiny. This logic makes no sense: why would humans be an exception when metabolic variation is observed everywhere else?

In the second part of this article, I will connect metabolism to its implications for weight loss. Weight loss is a topic a lot of people care about. Given that at least 75% of the U.S. is either overweight or obese, many can relate their own experiences of trying to lose weight. Even seemingly innocuous comments can generate enormous discussion. For example, the tweet below garnered a staggering 165,000 ‘likes’, easily exceeding even heavy-hitting stories such as Epstein, Iran, or tariffs:

losing weight is super simple: you just eat less https://t.co/dgYS3D3xWw

— stepfanie tyler (@wildbarestepf) July 11, 2025

But while nearly anyone can lose some weight temporarily through dieting, I posit individual differences of metabolism can explain why some people are much more successful at dieting compared to others. Consider the above tweet about “eating less”–as it turns out, having a faster metabolism means you can eat more without getting as fat. People often blame failed diets on a lack of willpower, but those with faster metabolisms need less willpower since they can eat more without gaining weight. When your body burns more calories, there’s more margin for error. You don’t have to worry that an extra ketchup packet or a small packet of sugar will derail your weight-loss efforts, since a faster metabolism can offset minor slip-ups.

Millions of people worldwide consume fitness/health content, such as popular videos on “how to get ripped” or “how to get abs,” but few achieve the sought leanness. Metabolism can in large part can explain why.

As I discuss this in detail in the post “Metabolism , fitness influencers, and looking good into adulthood“, many of these guys in their 30s or 40s who are persistently lean, although it can be explained by drug use, excessive cardio, or extreme dieting–metabolism is likely a key factor too, that all too often is overlooked .

I believe people intuitively know metabolism matters as much as they may posture otherwise, like the aforementioned Reddit discussion at the beginning of this post. On ‘fitness/health Twitter’, when the discussion of metabolism comes up, there are similar attempts at downplaying its importance or the existence of fast or slow metabolisms. When someone claims to have a fast metabolism or whose reported daily calorie consumption is indicative of a fast metabolism, the response by others is that the person is lying or miscounting. It invokes the same envy response as someone claiming to have a high IQ. This suggests people, correctly, at some intuitive level know metabolism matters for attractiveness and being lean, and that people with faster metabolisms are indeed privileged in this regard.

‘Fast metabolism’ is just another trait, like athleticism, attractiveness (such as facial bone structure), tallness, or high IQ, which confers status and other social benefits. The ability to ‘generate lots of waste heat’ or a heightened response to caloric restriction (ODS), is as genetic as the ability to have a ‘sub-4.5 second 40-meter dash’ or a ’40-inch vertical leap’. But whereas athleticism matters early in life, having a fast metabolism is useful for the rest of one’s life in terms of not getting fat and being attractive, long after high school or college. Because metabolism cannot be meaningfully raised, it makes sense to downplay it, compared to things which can be changed like physical activity level or diet. You cannot sell a ‘coaching plan’ to fix something that is unfixable.

Sure, ‘too much NEAT’ or ‘too much waste-heat’ will not earn one a Heisman trophy, but not being ridiculed on social media for having a fat profile pic is nice too. You cannot see waste heat energy like replaying an NFL highlight reel, but it’s every bit as genetic.

In practical terms, to give an example of how metabolism matters, the guy who is burning as many as 4,000 calories/day at rest (RMR) has 2x bigger metabolic furnace and hence much more room to cut calories compared to an otherwise identical guy who burns only 2,000 calories/day at rest to maintain his weight. Thus, the first guy will generally have an easier time losing weight and lose more weight given that his body is burning more calories. Starting at only 2,000 calories/day leaves much less room to cut without nutritional deficiencies and fatigue from eating so little. Or going back to the China study, the first guy effectivity has four free meals to spare compared to the second guy. These metabolic outliers at the far-right tail of the distribution are at a major advantage for weight loss, just as people with high IQs are at an advantage when it comes to learning, say calculus. Or >6’0″ guys at finding matches on dating apps.

An objection is, “If they are at the same weight, why does it matter if the first guy has a faster metabolism?” True, if they are both weight-stable and neither seek to lose weight, then it does not matter. But many people want to lose weight, for health reasons or for more superficial or cosmetic reasons, like being lean. Sure, health is a motivating factor, but people also want something to show for it, too. Imagine if both guys watch the same popular YouTube fitness video on “how to get abs” or “how to lose weight” and follow the same advice to ‘cut calories’, the first guy will generally find it much easier being that he has many extra calories (or meals) to spare compared to the second guy. Being that his metabolic furnace is 2x bigger, the weight will come off easier and faster.

Although the above example is contrived, this is not an exaggeration and is consistent with the aforementioned studies and abundant anecdotal evidence of people who burn fewer calories in terms of RMR than predicted by calculators (which are based off of regression equations) for their weight and activity level, or who otherwise stall despite counting their calories carefully. Some people have such slow metabolisms, likely due to genes, that the weight refuses to come off unless the calories are cut absurdly low, way fewer than predicted by RMR calculators.

For example, a user on HackerNews “HorizonXP” describes stalling out despite still being >200lbs and only cutting to 1,800-2,000 calories/day, which is low relative to his height and weight (about comparable to a woman, not an active 5’10” male). According to popular RMR calculators, he should be burning closer to 2,200-2,400/day for his weight, activity level, and height.

Another user “BizarroLand” relays a similar experience of burning fewer calories than predicted by calculators. This explained why he stalled at 250lbs, because he was too hungry to cut anymore, and yet the weight was not coming off due to having such a slow metabolism. When he went off his diet, he rapidly regained 20lbs despite not eating that much more.

On Reddit’s r/MacroFactor/, another user shares a similar story:

MacroFactor is an app that helps people track calories and develop meal plans based on some desired weight target and macro composition.

1700-1900 is very low, again comparable to a sedentary woman instead of an active male, and can explain why he stalled. He should be burning closer to 2,500 calories/day based on his stats.

These are hardly cherrypicked. There are enough examples that to include them all would necessitate a book, not merely a 3,900-word blog post. There are also people who have faster metabolisms, on the opposite side of the spectrum, as expected by a normal distribution.

It would be interesting to corroborate self-reported metabolism and calorie intake on r/MacroFactor/ with weight loss success. Do people with fast metabolisms (as I define as higher higher than predicted RMR for weight and height as predicted by regression equations) find it easier or are more successful at getting lean using the app? I predict they do. It’s reasonable to assume MacroFactor users are more careful about not miscounting, so the quality of data is likely better compared to typical self-reported surveys. Maybe this can be for a future blog post.

Yes, being more active can help with weight loss to some degree, but this also varies greatly individually, and the weight tends to return if the activity is stopped, which is common when life interferes, like work or family. Moreover, studies and anecdotal evidence also show a form of metabolic adaptation in response to exercise, called ‘adaptive thermogenesis’, so this means burning fewer calories at rest to compensate for the increased exertion. The Apple watch app may say you burned 400 calories from a vigorous run, but due to adaptation effects, it is closer to 100-200, or even zero for some especially unlucky folks. This has been studied in detail by evolutionary anthropologist Herman Pontzer, who developed the constrained energy model, which posits that the body downregulates its metabolism (such as reduced NEAT) to compensate for increased exertion, to keep the total daily energy expenditure below a certain threshold.

And then there is also the increased hunger reported by many after exercise, as many can attest:

Same on Twitter. There is tons of of anecdotal evidence of people failing to lose weight despite cutting their calories aggressively and doing tons of cardio, or who have to consume absurdly few calories to not regain:

I'm 5'10" and I've watched my weight since I was a teen. Aside from vanity, my hobby cycling hobby demands it. (Carrying five extra pounds up a mountain is a big, big deal.) Calorie calculators say I should eat 2,500 calories. I set mine around 1,500 and the weight fluctuates +/-…

— Bicycle Boy (@mcandrus) December 27, 2024

And:

He is lying about what he eats

— Haley🔥Shane | Traveling Brand Bard (@iamhaleyshane) April 26, 2025

Or on Reddit, here’s an especially unfortunate example of an obese man who only eats 1,600 calories/day but is unable to lose weight:

He says he counts everything carefully. Could be he still be miscounting? Absolutely. But none of the 150 comments considers the possibility that his metabolism might actually be that slow. Although having such a slow a metabolism is unlikely, it’s still consistent with the above studies. Putting his stats into a BMI calculator gives a value of 30.7, which is borderline obese. His RMR according to online calculators should be at least 2,100 calories/day. His claimed 1,600 RMR is about 25% below the predicted value for his stats, which would put him in the ‘hypometabolizers’ category. Although this is uncommon, the study showed 10% of obese fall into this category. Again, this example is not cherrypicked. There are many others like him on Twitter and Reddit.

In the replies, these people are often accused of lying or failing to adequately track everything. Yet burning so few calories, especially due to metabolic adaptation and having a low baseline metabolism to start with, is perfectly consistent with the literature of individual metabolic variability, which like everything else in life, follows a normal distribution. Yes, they could very well be lying or miscounting, but genetics are real. Some people must get the short end of the stick, or um, double helix.

Finally, I reviewed individual RMR test results shared on Reddit. Since RMR is measured in a laboratory by analyzing CO₂ output, unusually low values cannot simply be dismissed as errors in calorie counting. If a test shows a low RMR, it provides strong evidence of a genuinely slow metabolism. I performed Google searches such as “RMR reddit test /r/loseit” and “weight loss RMR dieting”. As I expected, many dozens of users across various dieting and weight-loss subreddits reported unusually slow metabolisms, with measured RMR values often hundreds of kcal/day lower than predicted by regression equations. More striking, however, was the absence of reports of abnormally fast metabolisms. This points to possible selection effects: individuals with faster metabolisms may find dieting easier, making them less likely to seek testing or share their results on Reddit. Here are some of these reports 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Example #2 is a late 30-year-old male who is 6’0″ and 215 pounds, whose tested RMR is 1600-1800 kcal/day. This is very low compared to his predicted RMR from calculators of 2,300 kcal/day for a ‘light activity level’.

Example #3 is even worse, at just 900 kcal/day RMR. After retesting, the “OP” still reported it was very low, “So I called back and they checked all the equipment and actually did another one later that day that had normal results. They confirmed that it was super low but I might have to see my GP for this. My thyroid was tested recently in a blood panel and in normal range. Bit at a loss about this, might have to eat accordingly.”

Example #4 reported a RMR 33% less than predicted by calculators, “I have quiiittteeee a bit to lose. Well over 200 lbs. My weight doctor sent me for RMR testing, as, while I am losing, it’s at a much slower rate than we’d like. I had the full, full metabolic panel, hormones, everything. I was even suspected of Cushings, but a local star endo said there was no way it was that. Nevertheless, after turning all other stones over, he sent me for RMR and the result was 1250 calories less than the predicted value. Does this indicate a metabolic issue of some sort, or do some people genuinely just have such poor metabolisms?”

Example #5 received very low values despite retests, “First, and a sad one, for me it confirmed what I was already pretty sure of: my metabolism is far lower than expected. My expected RMR is 2150, my actual RMR is 1650. So if I ate what I was supposed to calorie wise to maintain weight I would gain roughly 50 pounds a year (which Ive done at least 4 times in adulthood). I had pegged it around 1700-1800 so this wasnt a shock, but it’s also nice to know for sure.”

Example #6 “Got a basal metabolic rate test, told me it’s 523 calories below calculated predictions! Just a reminder everyone is unique and our bodies are complex”

Example #7 RMR is 300 kcal below expected value, “…but I got an RMR test (measured by oxygen consumption at rest), and it came out at *1100* – a full 300 calories lower than average, according to DexaFit. That’s an entire MEAL for me. I’ve been completely unable to stick to 1200/day since 2018 – I go crazy unless I eat at 1400 – but according to this, even *with* daily exercise, 1400 is MAINTENANCE. This obviously explains the weight gain. To back this up, I plugged my diet logs and weight into the adaptive TDEE calculator linked in another thread and it has me at 1380.”

Again, these are not cherrypicked, and to include all the examples I found would require an even longer post. All these people struggled to lose or maintain weight loss, and their low RMR could explain why they struggled. It was not miscounting, but that their bodies are hyper efficient.

People greatly underestimate just how much human diversity there is. When skeptics claim “It’s impossible to live on only 1,200 calories/day” or accusations of lying or miscounting, I’m like “You fail to understand how much humans differ.” The belief that the body cannot adapt to so few calories shows a lack of imagination of the spectrum of human adaptability and diversity. Humans are remarkably adaptable. There are stories of humans surviving in some of the most harrowing circumstances of extreme food scarcity.

This is not to say they are all obese or that dieting totally failed them. They lost weight, which is consistent with “CICO”, but now they stall at well-above their desired weight and are not lean. Or they can only not be obese, let alone lean, by recreating the Minnesota Starvation study, which sounds really unpleasant and unsustainable. There are simply too many instances of overweight people who are not losing weight despite counting calories for it to be written off as human error. It has something to do with metabolism–a sort of hyper-efficient energy-sparing mode or something that is impervious to lifestyle change.

Of course, there are other variables aside from metabolism, such as ‘hunger signaling’. Some people simply do not feel a ‘fullness sensation’ until they have eaten too much. The interplay between ‘the mind and the gut’ is somehow deregulated, so that the brain does not get the message that the stomach is full or that sufficient calories have been consumed. Or the stomach empties its contents too fast, leading to hunger too soon. But metabolism tends to set a hard line as to how much you can lose. You cannot lose more than you burn. Cutting below some threshold is not only unpleasant, but also potentially unsafe due to muscle and bone loss and various nutritional deficiencies.

Does this mean these people have bad genetics? Not really. It’s more like they have the genetics that served humanity well for hundreds of thousands of years, until only very recently. There is a sort of myth, promulgated by popular health influencers, that Americans in the 1950s were all skinny, and then fast-food came along during the ’70s and ruined everything. Americans have been gaining weight and trying (and usually unsuccessfully) too lose weight for as long as it has been tracked. Pudgy middle-aged people were pretty common during the ’40s and ’50s. It’s just that before the visually-driven modern era of social media, few cared or noticed. For much of human history, a propensity to being overweight would have probably been beneficial to survive famine. Now social media, especially post-Covid, has created a weird sort of artificial environment that favors those lucky individuals who generate too much waste heat, are picky eaters, or have heightened fullness signals, when for the rest of the history of humanity, this was a net-negative for survival.

But won’t GLP-1 drugs, like Ozempic, level the playing field? Sorta. Metabolism matters here, too. GLP-1 drugs suppress appetite, so like above, the guy or gal with the faster metabolism is going to still lose more weight. Similar to other weight loss interventions, there is extreme inter-individual variability in terms of how much weight is lost on GLP-1 drugs, with some individuals losing a lot (so-called hyper-responders) and others losing a little or none (non-responders). Yes, there are obviously other factors at play too, as these drugs seem to affect the brain and behavior, too. But I posit people with slow metabolisms relative to starting weight, yet still obese, find it hard to lose enough weight, even with the help of these drugs.

For example, consider a seriously obese person (BMI>40) who eats 6,000 calories/day due to a binging disorder brought upon by a sudden setback in life, compared to someone who eats ‘only’ 3,000 calories/day to maintain the same weight and has always struggled with obesity his or her whole life despite not eating ‘that much food’ (such variability is again consistent with the aforenoted studies). We’re assuming again the two individuals are weight-stable, so they are neither gaining or losing weight at their caloric intake. The first person with the faster metabolism will be at a big advantage, owing to simply burning more calories at rest, so the differential/deficit is greater under calorie restriction induced by GLP-1 drugs.

When people tell their weight-loss stories using GLP-1 drugs, there is no mention of metabolism or starting calories. Is this obesity in the context of a binging disorder or of short onset, or a lifelong struggle at obesity even when not eating that much or even when dieting? Those on social media who get shredded or otherwise lean on GLP-1 drugs may have fast metabolisms to begin with, which when combined with the calorie restriction induced by these drugs, leads to large, impressive weight loss. Although these drugs make it easier to diet, metabolism is still a major factor as to how much weight is lost.

In conclusion, in the first section, there is compelling evidence that metabolism differs greatly among individuals, when controlling for factors such as weight and height, which cannot be explained by any obvious phenotypical factors. I also posit that this also plays a role in weight loss, such as the degree of metabolic adaptation or how much room to cut calories without dangerously starving oneself. Part of what motivated me to write this post was my own weight loss journey and reading about other people who lost weight or struggled, and why some succeeded and most failed. In the latter, such individuals are often admonished for failing to cut calories enough or not moving enough, but seldom is the role of metabolism ever considered, or it’s dismissed . If the body simply refuses to burn enough calories despite everything else being done, there isn’t much you can do.