An epic-sized article by David Brooks: How the Ivy League Broke America: The meritocracy isn’t working. We need something new.

The good test-takers get funneled into the meritocratic pressure cooker; the bad test-takers learn, by about age 9 or 10, that society does not value them the same way. (Too often, this eventually leads them to simply check out from school and society.) By 11th grade, the high-IQ students and their parents have spent so many years immersed in the college-admissions game that they, like 18th-century aristocrats evaluating which family has the most noble line, are able to make all sorts of fine distinctions about which universities have the most prestige: Princeton is better than Cornell; Williams is better than Colby.

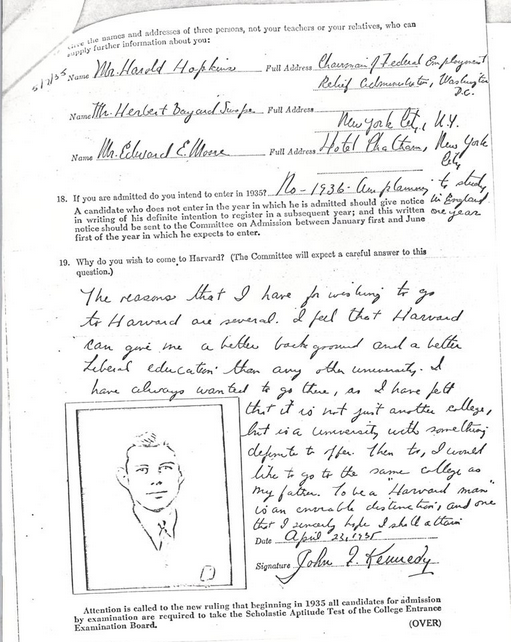

The WASP gentry-class has simply been replaced by the overeducated elite-class, whether in the Bay Area, in the technology industry, academia or journalism, or on Wall Street. It’s more meritocratic and diverse, but it’s implicitly IQ that is the filtering mechanism, not pedigree or lineage. More demand and lower acceptance rates for elite schools means the average IQ of the student body goes up. Below is the essay produced by JFK to apply to Harvard in 1935 (being that his essay filled the allotted space, it was not expected to be longer). By comparison today’s Harvard applicants need top test scores on everything, and a much more impressive essay on top of that.

Same for the job market, in which employers have lots of ways of implicitly filtering out less intelligent employees even if IQ testing is technically ‘banned’, such as background checks, multiple rounds of interviews, automated resume filtering, personality tests, or phone interviews. Higher wages plus lots of applicants means employers are economically incentivized to be extremely choosy. As anyone can attest on Reddit’s economics or quant finance subs, or on the popular message board Econ Job Rumors, getting a job in finance is harder than ever in terms of competition, the required credentials, and of course, lots of interviews and other screening.

Both of these trends seem consistent with the meritocracy. More screening and competition generally implies better-qualified applicants being chosen. However, political correctness or indoctrination are often blamed for the overreliance on college degrees. As the narrative goes, employers want politically correct employees who have been sufficiently brainwashed or indoctrinated, so college is an effective filtering mechanism in this regard. This runs in opposition to the meritocracy.

As discussed earlier, this narrative is unconvincing. Employers value college because of the competence it signals more so than political correctness. Due to lowered standards and inflated graduation rates for high schoolers, there is a so-called ‘college cliff’ that describes the abrupt differential of assessed competence between the median high school grad vs. the median college grad. Many of the skills ‘we’ take for granted, like the ability to write cogent sentences, are otherwise in short supply or highly unequally distributed even in spite of claimed ‘elite overproduction’. If you’ve ever been on a medical forum after searching Google for symptoms, you’ll notice the typical person (as everyone gets sick or has symptoms, it’s not an environment that self-selects for IQ) writes poorly.

Second, it would cost much less money from the perspective of employers to simply hire woke high school grads than to pay the college wage premium, if political correctness is the sole criterion. Prima facie, this represents a major inefficiently for companies to pay 2-3x more for college grads when there are plenty of woke high schoolers.

It’s not like only people with college degrees list their preferred pronouns on their social media accounts or post BLM or LGBTQ+ flags or emojis–there are no shortage of under-educated people who hold woke/progressive values. Similarly, it would cost much less for employers to do the indoctrination themselves than to have to rely on colleges to do it. This is what companies already do, like orientation. A notable example is Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater, in which employees are indoctrinated into a sort of culture that centers around its enigmatic but opinionated septuagenarian founder. However, trying to bring a borderline illiterate or otherwise low-IQ employee up to par is too expensive or futile, hence filtering for degrees is easier and cheaper in spite of the premium. In the aggregate, bad employees cost more in terms of mistakes or being ‘slow to catch on’ than the windfall of good employees.

Are today’s elites better? It’s hard to say, but I find the argument that they are less competent to be unpersuasive. Technology elites seem to show no signs of stagnation, such as AI, smartphones, or apps. There is still innovation and a meritocracy that is more or less extant despite the occasional token diversity hire or paeons to wokeness. With all the filtering going on in the hiring process, such as difficult interviews and credentialism, this lends credence to employees being more competent, not less.

True, there was incompetence during Covid by policy-elites, such as the NYC nursing home fiasco. But 20 years earlier, during 9/11 after the first plane hit the North Tower, the ill-fated decision was made by the New York Port Authority for occupants in the South Tower to not evacuate and to return to their offices; as we know in hindsight, this doubled the casualty count. Hell, the Titanic didn’t even have enough lifeboats for everyone…something so obvious. Or in regard to the Hindenburg, filling a passenger airship with a highly flammable substance. Even if having insufficient lifeboats was intentional, the hull of the Titanic was unusually thin and brittle due to the ice water and manufacturing process, which engineers had not anticipated. Incompetence has always existed for as long as people have faced uncertainty or incentives create conditions conducive to it.

(From 1901 to 1921, every American president went to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton.)

That is quite some impressive cherry picking. We’re talking only 20 years and 4 presidents. 100+ years ago there were also far fewer colleges on a per capita basis compared to today. This is what we would expect.

The author is also too dismissive of predictive value of high IQ, citing the Terman study and a second much later study by Vanderbilt:

Similarly, in a 2019 paper, the Vanderbilt researchers looked at 677 people whose SAT scores at age 13 were in the top 1 percent. The researchers estimated that 12 percent of these adolescents had gone on to achieve “eminence” in their careers by age 50. That’s a significant percentage. But that means 88 percent did not achieve eminence. (The researchers defined eminence as reaching the pinnacle of a field—becoming a full professor at a major research university, a CEO of a Fortune 500 company, a leader in biomedicine, a prestigious judge, an award-winning writer, and the like.)

The Terman study is often cited as an example of the claimed shortcomings of genius. It’s such a weak argument that only shows the statistical innumeracy of whoever uses it.

So what about the control group? What have they accomplished? Eminence is so rare, even among people who are smart. Being smart bumps the odds, but the odds are already so small to begin with, so this is exactly what one would expect–most people regardless of IQ do not get much recognition. There is not enough attention to go around for everyone to get the credit or recognition they are owed or commensurate with his or her accomplishments. The idealization of success as being on the cover of Time or a billionaire, is a rather myopic or limited conception of what it means to have a productive life. It also makes the implicit assumption that everyone is motivated by status, fame or material gain, when many people are not.

It’s not like John Carmack was the only person who developed those games, but he gets most of the credit for having created Doom, among other titles. Early Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold is not a household name despite objectively being as smart as his boss, such as being a child prodigy who attended college at 14 and studied physics at UCLA. Does this mean IQ does not matter? Not at all; Microsoft employees, on net, are all smart (every prospective employee at least up until 2000 was at one point personally interviewed by Mr. Gates himself), but there can only be one Bill Gates or one Steve Jobs.

Overall, I think the meritocracy is more or less working, but it’s not as equitable as some may want. There is the perception that colleges act as unelected gatekeepers to the middle class. Many high-IQ people are thriving, such as tech or finance, but those who are in the middle may be falling between the cracks, as they lack marketable skills or the aptitude to attain them. More alternatives are needed than just ‘the trades’ or the service sector for those without degrees. Additionally, credentialism is not antithetical to the meritocracy; it’s just another filtering mechanism at predicting who is more meritocratic. But at the same time, as mentioned above, in a free market it makes no sense for employers to voluntarily pay the college wage premium when there are far cheaper alternatives.