When one thinks of a hard subject, often what comes to mind are ‘STEM’ subjects, (e.g. math and physics), not the humanities, which are assumed to be more subjective and less rigorous. But such impreciseness also makes the humanities harder in some ways. Objectivity creates boundaries and rules, which can be generalized and repeated. A hypothesis can be falsified. A conjecture can be disproven with a counterexample. As hard as calculus can be, there are immutable rules that underly it, which can be taught and reproduced. There is only a single ‘chain rule’; the concept is culturally invariant, even if the notation occasionally differs.

The rules-based nature of mathematics provides a more structured path to competency. Mastery of writing requires not only a lifetime’s worth of vocabulary acquisition and the ability to use it appropriately, but broader cultural literacy that simply can’t be taught.

— Cosmopolitan Reactionary (@cosmorxn) October 25, 2024

I agree (the entire twitter-thread is excellent). Having done both, math is more rule-based, although it does require the occasional epiphany to clear an impasse.

But what makes art or any other expression of creativity ‘good’? I think goodness is measured by how other people receive or perceive it, not the intrinsic qualities of the ‘thing’ in and of itself. That it–goodness is subjective and entails peer approval. A good book is a best-seller, or gets favorable reviews even if it does not sell well. The Mona Lisa is good because of its historical significance, not because it’s the most aesthetically pleasing painting ever in any objective sense.

Does writing fail because the premise/thesis is bad, the writing itself is bad, or the author is bad? Disentangling these is hard, if not impossible. Michael Crichton famously attempted to answer this by turning in an essay originally by Orwell for a Harvard class and only getting a ‘B-‘, from which he inferred that the problem was his teacher, not him.

Creative writing is hard because there is no obvious market or audience for it. If I write a math book, I know that my target audience are people who want to learn math, or more specifically, the concepts in said book. If I write a how-to guide on golf, my market is golfers. Intro calculus classes will continue to be the bane of many of freshmen now and probably for the foreseeable future. In spite of AI, teachers can adapt by requiring students to show their work, or an emphasis on in-class assignments and quizzes. But who or what is the market for short-form non-fiction about ‘vague feelings of ennui’ or ‘disillusionment with modern society’? Who knows.

For this reason there is no way to ‘focus group’ creative writing. Unless the title contains the words “Harry Potter”, fiction is hit or miss, mostly miss. Publishing houses know that every new author is a gamble, and even famous authors occasionally produce duds. Marvel/Disney can predict with a high degree of certainty that the latest installment of a superhero franchise will succeed with moviegoers between the ages of 15-30, but this does not work with writing, which is based more on sentiment or mood than need, want, or desire. There is a built-in, captive audience of people who will set aside 2-3 hours of their weekend and $30 to watch movies. Same for TV, such as serials. But people do not need books or blog posts, nor will go out of their way for them.

Also, creative writing is not about responding to what the customer wants, like with sales, but more like decoding the reader’s ‘value system’, which is harder and less precise. “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses” is a famous quote attributed to Henry Ford, at the apparent uselessness of market research. Well, after solving that initial problem, Ford became wealthy selling lots of cars. What does the reader want? A good writer can ‘read’ or anticipate that which the reader feels is true but cannot articulate or put his or her finger on. But this is harder than just producing cars on an assembly line, as reader tastes are not need-based but instead more value-based.

This is why shared narratives are so powerful and useful. It’s hard to have an opinion that can withstand scrutiny, no matter how much evidence you supply. Getting the facts right is hard enough, let alone having good opinions. Shared narratives are like ‘anchor points’ that a broad but discriminating audience can relate to, that has a lower burden of proof than taking a side or having to dig into a position.

For example, many people are distrustful or suspicious of government, or believe that ‘Western society’ is in decline/decay, or that elites are perfidious or opportunistic. Successful writing taps into this sentiment by conveying these inchoate feelings into something concrete in writing. “You read my mind!” is the desired reaction. Better yet, shared narratives are time invariant. Distrust of authority figures is as old as civilization. Even in the ’90s, during one of the strongest economic expansions ever, Congress was still held in low regard by a lot of people on either side of the aisle. There is always the perception that those who have been entrusted with power are abusing it.

As another example, “Are index funds better than stock picking?” Rather than having to take a side, the shared narrative is to argue that the financial media tends to sensationalize things. This is something that almost all investors can agree on.

Additionally, short-form writing needs to be one-hundred percent dialed-in to succeed. People will forgive a movie that has dull parts or inconsistencies in the plot. Otherwise Hollywood would not exist given that ‘boring parts’ and plot holes are endemic to all movies, even classics. But readers are unapologetically unforgiving with short-form writing. A bad/awkward turn of phrase, unfounded assumptions, logical inconsistencies, inaccuracies, etc. can strangle the writing in the crib and compel the reader to quit well before getting to the end and being implored to “share and like,” which they certainly won’t.

Or to bring this back to math, it’s not fatal if a proof is hard to follow or even has errors provided the final result is correct by being independently verified. In this case, the original discoverer will get credit for the result, but others will share credit for finding better proofs or improving on the original result. Writing is harder in this regard in that the conclusion is less important than how the argument is structured or the prose.

A Google search of the phrase “I stopped reading here” gives thousands of results, but how inclined are people bail on a movie or a TV show as readily compared to writing? Hardly, even though movies and TV shows are a much bigger time investment than a blog post or an article. Or in other words, readers have much higher standards for writers than moviegoers have for directors, actors, and screenwriters. [I think most people who proclaim they stopped reading actually do read further, but just say that as clever-sounding retort.]

This can also be explained by the sunk cost fallacy. Compared to a free blog post or article, a movie ticket is like an investment, and cutting one’s losses by walking out is an admission of having made a bad choice. We like to think of ourselves as rational, informed decision makers with perfect information. But you already paid for the ticket; nothing is gained by wasting your time as well.

Moreover, language is something we take for granted, which I think can explain the dismissal of the humanities compared to the ‘hard’ sciences. Yet there is a chasm-wide difference between spoken language and written language. Writing, unlike speech, requires a sort of concision (althoguh this should not be confused for brevity) or logical flow. The ‘ums’ ‘ahhs’ and other filler in spoken language is tolerable to the audience, but with the exception of some fiction, readers have much less patience for this. A blog post that does not get to the point, or cannot make up its mind as to what the point actually is, will be met with an expeditious click of the back button, but for some reason we can sit in rapt attention as someone drones on during a podcast, or a politician who goes on needless digressions during a speech.

For the above reasons, good writing is one of the hardest things ever, or at least why the intellectual barriers for mastery at the craft are so high. So few individuals can do it, including those who we can assume to be smart based on qualifications or non-writing accomplishments.

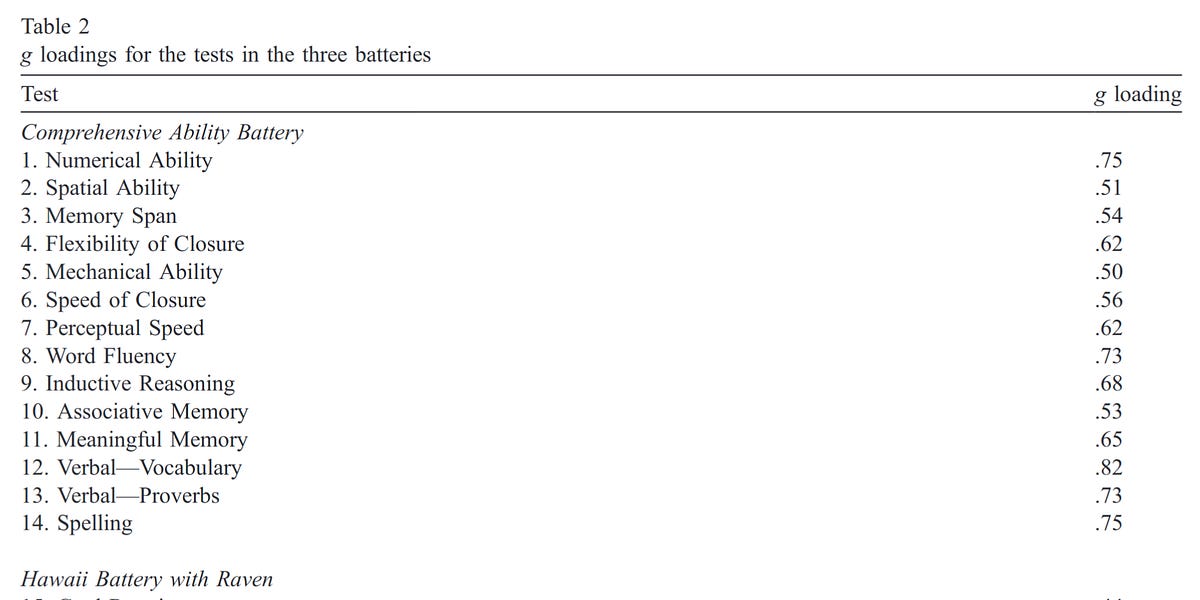

This is also corroborated by IQ tests. The vocabulary component of a full-scale IQ test has among the highest ‘g loading’ of any of the sections, at .82, which is even higher than numerical ability (only .75):

People who we can reasonably assume to be smart and accomplished, such as CEOs and scientists, generally do not write their own books or op-ed articles, but instead rely on an extensive underground network of ghostwriters. Sure, some of this is due to businesspeople having more important things to do than write, but given how prominent VCs and other businessmen apparently have hours to burn everyday arguing about politics on Twitter or going on each other’s podcasts, I don’t think time is the main obstacle. Same for Richard Feynman, regarded as one of the smartest scientists, whose books were ghostwritten:

“Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!” (1985) is a memoir based on conversations between Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman and his friend, American biographer Ralph Leighton. The stories Feynman told were recorded by Leighton and edited by Edward Hutchings. The rights to the book, written in the first-person singular, are owned by Feynman and Leighton.

Warren Buffett is 94 years old…he had a lifetime to write a book. Never got to it. Same for his right-hand man Charlie Munger (his Almanac, also ghostwritten, does not count), who died book-less at 99. Maybe Buffet found it too hard, as smart as he is, or he has more important things to do, like ‘maximizing shareholder value’.

As a caveat, I don’t count his shareholder letters. There is a built-in audience, his shareholders and fans, who will read his letters and find them valuable on that basis alone. Unlike op-eds, blog posts, or creative writing, he’s not trying to persuade a skeptical audience or trying to convey some sort of sentiment or belief about something, which is harder than writing as a matter of-fact about his company.

Like Buffett, I too have a knack for investing and stock picking, for example having invested in Meta/Facebook stock in the low $30s in 2013. I can see myself doing Buffett’s job and succeeding at it. But good writing is on another level of unattainability. It’s truly like a craft more so than a science in that it’s like sticking a bunch of ingredients into a black box and hoping for the best, but at the same time, the outcome is not random; there are obviously people who are much better at it than others. To those people you have my awe and respect.