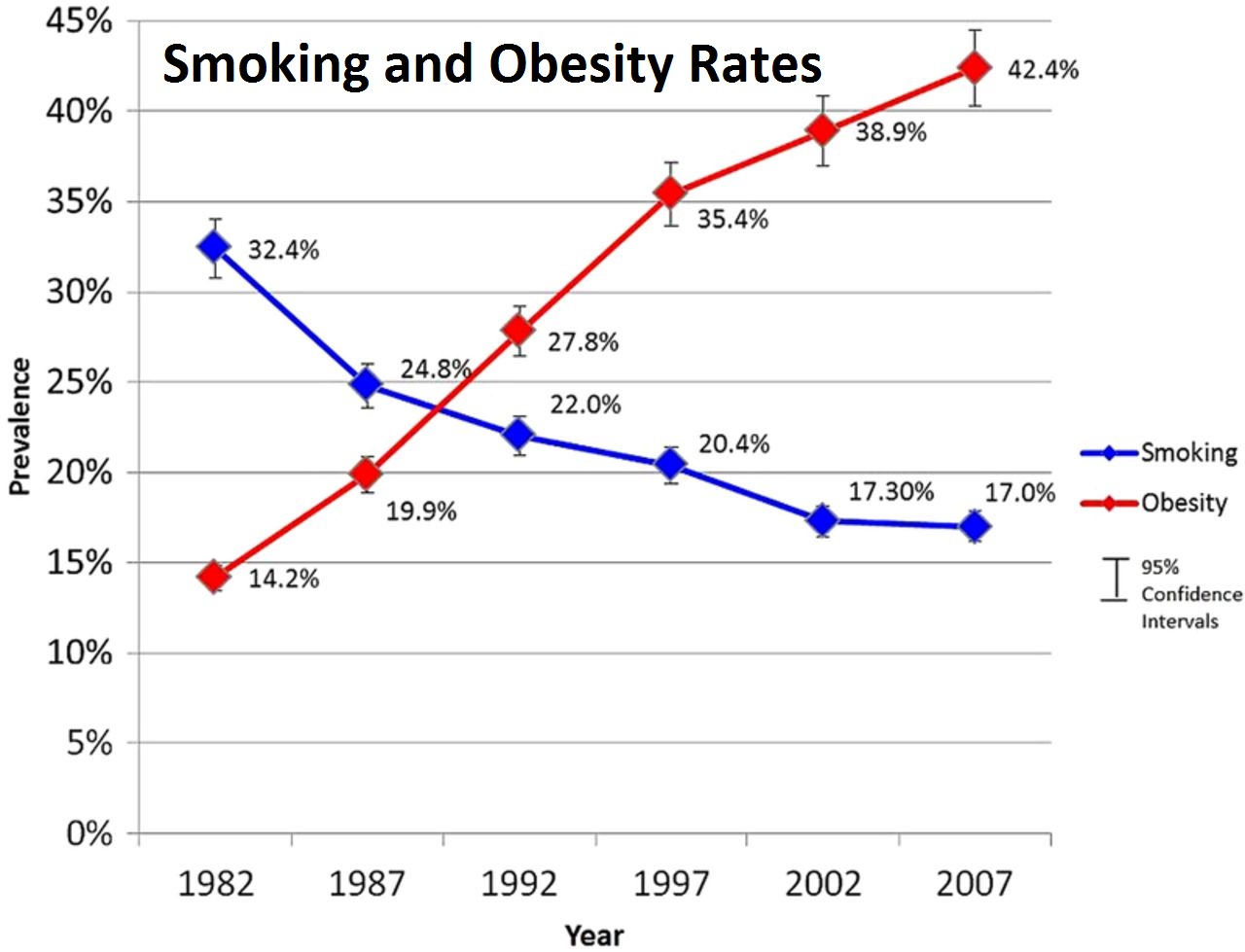

The apparent post-’70s rise of obesity in America can be explained the decline of smoking. The decline of smoking inversely matches the rise of obesity almost perfectly:

I can attest in the ’90s and early 2000s it was common to see pedestrians smoking. Cigarette butts littered the sidewalks and accumulated in small mounds or dams around storm drains when it rained.

Fast-forward to the 2010s and I cannot recall the last time I saw someone smoking, and the cigarette butts are gone too. It’s like in the span of a couple decades this habit which afflicted tens of millions of Americans was eradicated, compared in the mid-20th century when smoking was an inescapable part of American culture, glamourized by the entertainment industry and endorsed by the biggest celebrities of the era. Smoking was so ubiquitous that even US military rations included cigarettes, a practice which stopped in 1975.

Today it would seem smoking is perceived as the opposite of cool or the ultimate social faux pas, as an outward indicator of low social status and an advertisement of one’s conscious and open disregard for his or her health and those affected by the secondhand smoke. At the same time, the rise of ‘fat acceptance’ has made society more tolerant of obesity.

Whereas smoking has disappeared, on social media one not uncommonly sees people feasting on fattening food at restaurants that are known for notoriously high calorie counts, like at Cheesecake Factory, or while watching TV. It’s not like the consequences of obesity are not well advertised, yet people continue to overeat in light of this. This suggests a major shift in consumer tastes, likely choosing food over more dangerous or contraband habits like smoking or hard drugs.

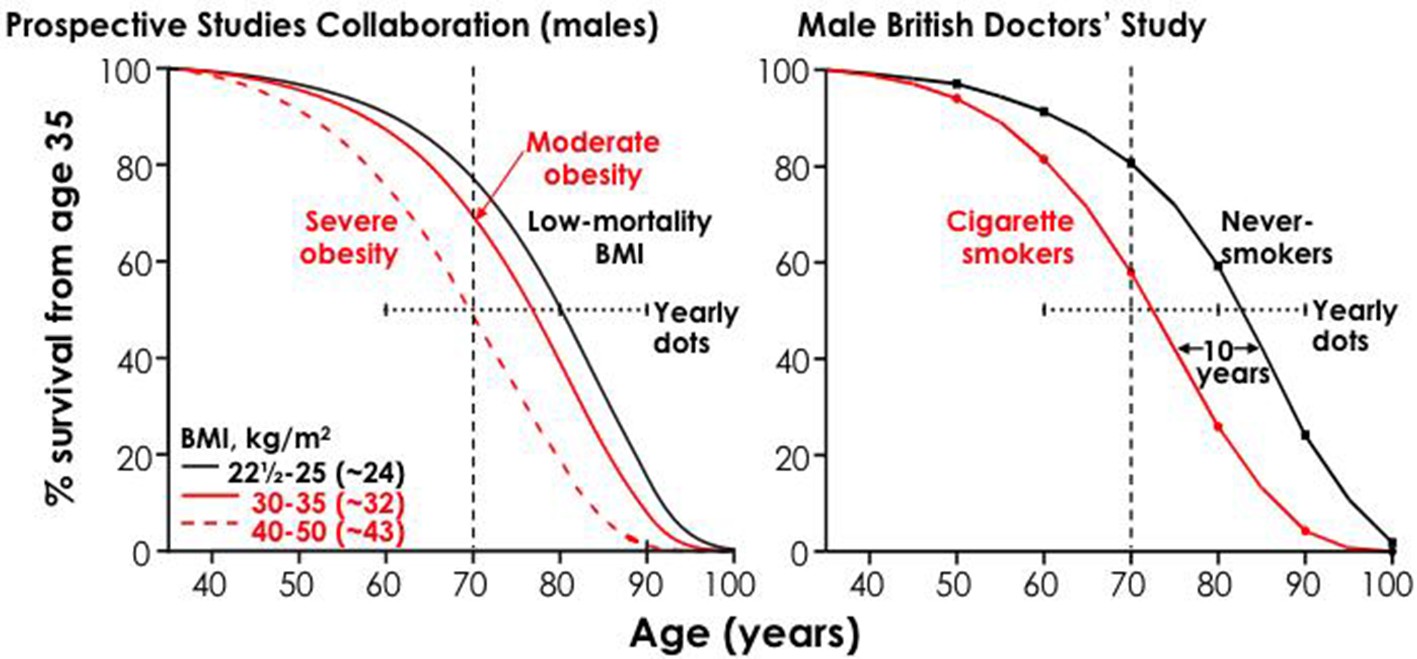

In my post The Rational-Consumer Explanation for Obesity, I argue that Americans are swapping out an unsafe habit, smoking, for a safer and de-regulated one, that being food. Moderate obesity (a BMI between 30-35) lowers life expectancy by only 2-5 years, compared to 10 years for heavy smoking ( > 1 pack a day):

Smoking attenuates weight gain in three ways: As a substitute for snacking whilst giving that much-needed dopamine rush, suppressing appetite, and by slightly raising one’s metabolism by about 10%. Given that a small caloric surplus over a long time leads to obesity, this can make a difference over many decades in terms of mitigating energy surplus and weight gain. Consequently, quitters gain weight, and the nicotine addiction makes quitting difficult for a lot of people, in much the same way people find it hard to stop eating unhealthy food.

[The delivery of nicotine by smoking leads to vasoconstriction and the ‘cool’ or relaxing sensation that is attendant with smoking, and explains why patches, gum, vaping and other nicotine-delivery substitutes are not very effective as stimulants. The pleasurable and instant delivery of nicotine is only in its most dangerous form, smoking.]

Amphetamines saw widespread civilian use after the Second World War to treat depression or as an appetite suppressant. Similar to GLP-1 drugs, amphetamines, which came in a distinctive rainbow color, could be obtained at walk-in pharmacies with no questions asked. This was during the fifties, a time assumed to be ultra-conservative, yet hard drugs were readily available.

Today, amphetamine and its derivatives, like phentermine and ephedrine, are tightly controlled substances. In McBee’s day, they were business as usual. She is credited with helping expose the magnitude of the United States’ amphetamine use—normalized during war, fueled by weight worries, and prescribed with almost reckless abandon until the 1970s.

There was also a bargain, low-tech version of Ozempic, Syrup of Ipecac, which although now discontinued at the time was a common way for people to lose weight by inducing nausea and vomiting, similar to the side effects of Ozempic and related drugs. Purging works for weight loss because it fools the stomach and brain into thinking it is satisfied, yet the body does not register being as hungry after the food is purged. So you can eat a thousand-calorie meal, and soon after purge half of the calories and still feel about equally full or only slightly more hungry afterwards. This is not to endorse smoking, speed, or purging, but I am explaining the common ways people, especially celebrities, stayed slim in the ‘pre-obesity era’.

This crackdown on amphetamines coincided with the start of the obesity epidemic in the US, at around the early seventies. It would seem like two addictions, stimulants and smoking, were merely replaced by a third, food. And whereas stimulant abuse can sometimes produce a characteristic model-like gauntness that some may find aesthetically pleasing, weight gain is almost never attractive.

Food does have stimulative effects, as anyone who has bitten into a sugary snack can attest to the rush of flavor and energy that hits as soon as the palate makes contact with the food. It does not have to be sugary food–a fatty steak will produce a similar effect. This is why offices not uncommonly have cafeterias stocked with food, typically sugary snacks, and 24-7 meal service provided by the larger tech companies, an example being Google and its legendary meal programs.

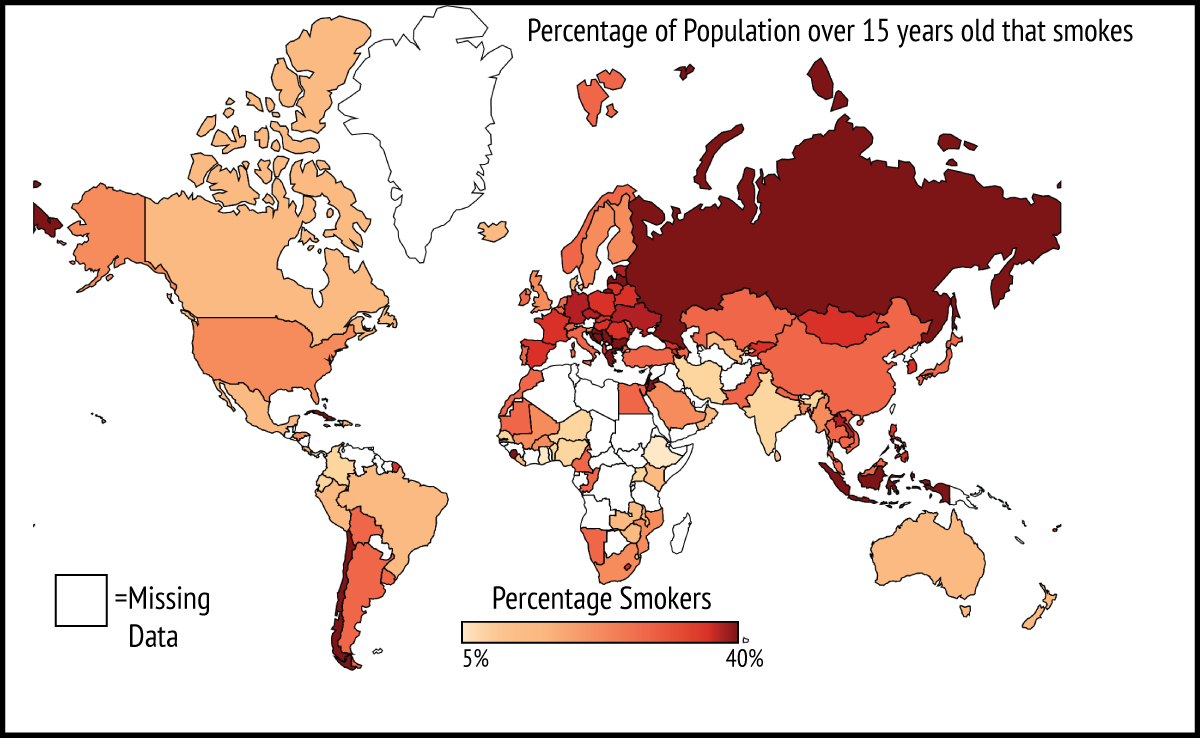

Outside of the US, smoking is more common, which can in part explain America’s higher obesity rate compared to elsewhere:

Although smoking hasn’t gone way completely in the US, as the above map shows, various smoking bans and social stigma means smokers need to be covert and strategic about where they choose to light up.

Whether it’s suppressing appetite, boosting metabolism, making people more sociable and outgoing (sharing cigarettes is a great icebreaker), and for both its calming and mentally-stimulative effects (typically, drugs can do either but not both), smoking makes life better in every respect (except for the whole lung cancer and COPD part of it, and discarded butts everywhere). If that is not enough, smoking can even help solve the national debt. Smokers also die sooner, helping to reduce medical spending and social security spending in old age.