I saw this tweet going hugely viral:

"1990s middle class lifestyle" means 3-bedroom house, 2 cars, annual family road trip holiday, every 5 years overseas holiday, the 2-3 kids go to solid 4-year colleges, something like home roof repairs is financially non-catastrophic.

In 2022 I've described a 400K/yr+ household.— Jacob Shell (@JacobAShell) December 19, 2022

Many people took issue with the claim that a 3-bedroom home costs $400k. It depends where.

It’s taken as a truism or foregone conclusion by the media and pundit-types that the boomers have it easy compared to gen-z and millennials, who are condemned to Dickensian existence of substance wages and posting memes for entertainment.

But it may come as a surprise to some that despite Boomers having decades of post-war economic prosperity and cheaper homes, still, 33% of boomers have no retirement savings vs. 44% millennials, so it’s not like the difference is that big given how much of a head start boomers had. Another source purports that 45% of boomers have no retirement savings:

Research by the Insured Retirement Institute (IRI) from 2019 also suggests trouble for many retiring Boomers. IRI found that 45% have no retirement savings. Out of the 55% who do, 28% have less than $100,000. This suggests that approximately half of the retirees are, or will be, living off of their Social Security benefits.

So much for boomers having it easy or always being wealthier. Sure some are, but there is considerable generational overlap, as expected when comparing large groups of people. Boomers and gen-x not uncommonly fill the ranks of the lowest-paying of service sector jobs (although some of this is for benefits such as healthcare). It’s like, “Why are not you not conforming to the media narrative of being so much better off? Why are you not drawing equity off the home you bought for the cost of a postage stamp, instead of scanning items at Costco?”

And from The Atlantic, The Myth of the Broke Millennial:

By 2019, households headed by Millennials were making considerably more money than those headed by the Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, and Generation X at the same age, after adjusting for inflation. That year, according to the Current Population Survey, administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, income for the median Millennial household was about $9,000 higher than that of the median Gen X household at the same age, and about $10,000 more than the median Boomer household, in 2019 dollars. The coronavirus pandemic didn’t meaningfully change this story: Household incomes of 25-to-44-year-olds were at historic highs in 2021, the most recent year for which data are available. Median incomes for these households have generally risen since 1967, albeit with some significant dips and plateaus. And like each generation that came before, Millennials have benefited from that upward trend.

This agrees with what I have been saying for years, which is that millennials and gen-z are not always poor, as commonly assumed by the mainstream media. The media only focuses on the poorest third or so of young people, ignoring or overlooking those who are much more successful. Not everyone under 30 is $200k in debt to study art history. Salaries for professional middle/managerial-class (PMC) jobs, such as consulting, have exploded since the 2009 lows, even when adjusted for inflation and student loan debt.

Regarding the economy and society, the boomers still had to contend with the high inflation of the ’80s and ’90s, the stagflation and oil crisis of the ’70s, the Cold War and the ever-present threat of ‘MAD’, the crime wave of the ’90s, the early ’90s recession, and the early 2000s recession and the subsequent severe bear market of 2000-2003. Homes were cheaper, but mortgage rates were also much higher, and salaries much lower. Millennials in the early 2010s had the benefit of historically low interest rates, which made mortgages more affordable even if homes were more expensive (although with mortgage rates surging, this trend may finally be reversing).

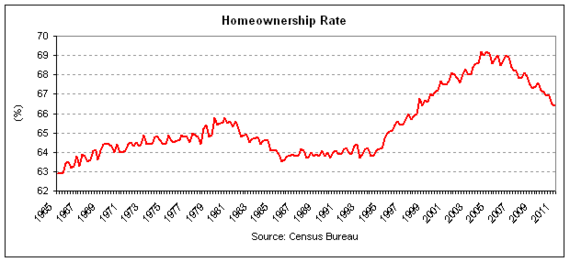

Indeed, in spite of boomers having much cheaper homes, the home owership rate has actually increased over the past half century:  (Don’t tell the media this!)

(Don’t tell the media this!)

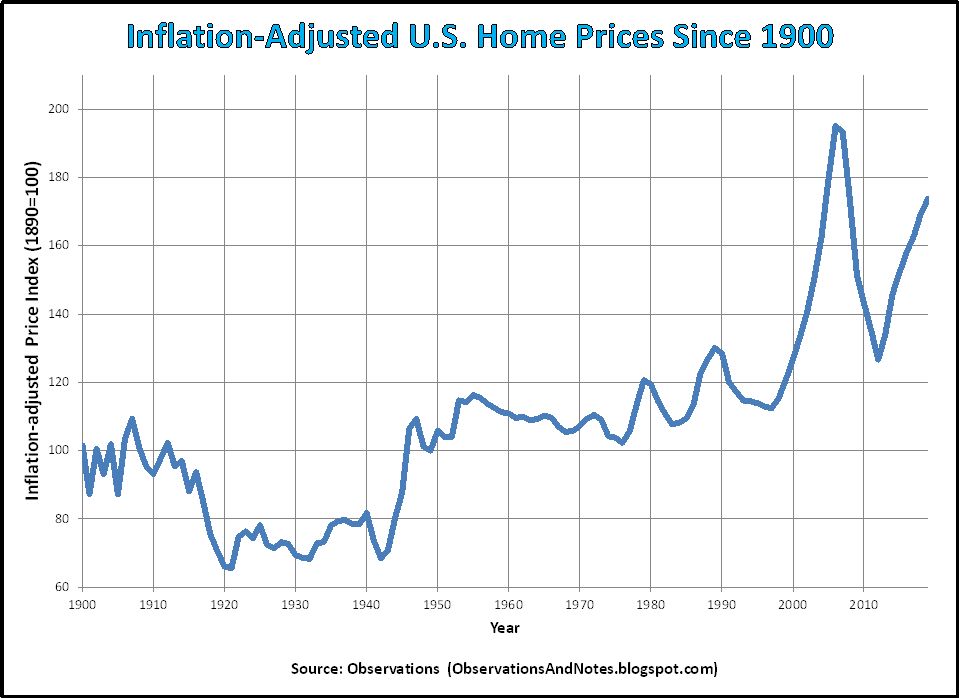

Also, homes had much less appreciation back in the boomers’ era. Yes, homes are so expensive today, but if you can actually afford one, it immediately becomes a wealth-generating asset with strong real returns. But from 1950 all the way until around 1995, ‘real’ home prices were unchanged:

The notion of homes being investments instead of merely dwellings is a relatively new development. Because homes are such a large investment and major part of the US economy, such as consumer spending, policy makers have a strong impetus to enact policy that benefits homeowners, and create conditions conducive to home ownership. Home prices surged during Covid, when it seemed like the Spanish Flu all over again. And after 2010, when it seemed like the US economy has been obliterated beyond any hope of recovery. It may seem wrong or unfair that the arc of policy is designed to perpetuate a system that reinforces its unfairness, but I do not see any reason for things to change. It’s always the same pattern: a crisis comes along, and pundits predict that there will be a new, more egalitarian status quo or lower prices, and instead the old trend resumes, but even stronger thanks to stimulus and low interest rates.

In spite of the college-educated barista trope–a favorite of pundits when making a sweeping generalization about an entire generation–the data has consistently shown that college grads make more than high school grads and this gap has only widened since 2008. So although college is more expensive, so are the returns even adjusted for inflation and debt.

Rather than all young people struggling, it’s more like a barbell of two extremes: young people who are doing really well, such as the PMC, and those who are struggling. Economic conditions and social trends over the past decade have allowed some young people to become way richer than earlier generations, thanks to the scalability and network effects of high-tech industry, but at the same time, for those who cannot joins the ranks of the PMC or are unable to find success on YouTube or ‘hustle culture’, things may be worse, especially due to expensive homes and high rents.

I have observed that whereas boomers may have had more total wealth compared to later generations, that millennials and gen-z have a much thicker right-sided tail in terms of individual wealth. Boomers and Gen-x had fewer opportunities to make money compared to talented young people of today. Professional careers were less lucrative generations ago, even after accounting for inflation and student loan debt. Sure, boomer rock stars made a lot of money, but the record labels took much of it. Pro athletes made much less on an inflation adjusted basis too (not the $50+ million contracts like we see today).

In the sixties or seventies if you were good with numbers maybe you got a job at IBM or Bell Labs, which paid the equivalent of $80k today, not $300k+ (plus stock options) like at Google or other big tech companies today. Docs didn’t make that much either. Only starting in the 1990s did doctor salaries explode. One can argue that not all tech companies pay as well as Google or Netflix, which is true, but IBM was considered the Google of its time.

Consequently, thanks to fat salaries and surging home prices, there are a plethora of stories on Reddit and Hacker News of millennials and gen-z who bought homes 5-10 years ago and are now sitting on a fairly large nest egg of home equity. After factoring in strong stock market returns, such as the 2009-2021 bull market–among the biggest ever–means even more wealth, magnified by a backdrop of low interest rates and low inflation.

Overall, there are more opportunities than ever for talented millennials and gen-z, even compared to boomers and gen-x matched by age, but more inequality too. Attaining a middle-class lifestyle often means clearing important hurdles such as a college degree and home ownership, which have become more expensive but at the same time more lucrative.