A week does not go by without headlines decrying the sorry state of America’s education system, such as stories about how U.S. students are either falling behind foreign peers or are failing to meet basic proficiency standards. Or how high school students cannot do algebra. Or college students being unprepared.

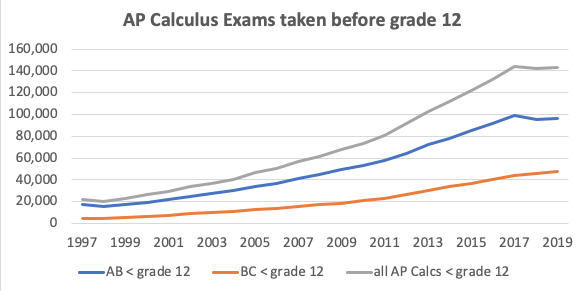

Seeing such headlines, one may be under the mistaken impression that all or most American students are on aggregate pretty dumb or are struggling, and a lot of them are, but many are not. For example, it used to be that only 5% of high schoolers learned calculus, but now 25% or more do. Same for the growing popularity of AP courses:

The media ignores this and instead focuses on the laggards. It’s like you got one half of society that cannot do arithmetic, and then the top 5% who are competitive and pulling way ahead. It shows how important possibly innate factors are. No matter how hard educators try to instill algebra, a certain fixed percentage will never get it.

Who are these kids who are unable to do algebra? Where do they live? In another universe? I remember seeing stats about Covid deaths, but I don’t know anyone who has died of Covid, nor do I know anyone who knows someone who died of Covid. Surely they exist, but why haven’t I seen them? These underachievers are apparently not online, because online it seems like everyone is super-successful and competent. It’s like there is this huge epidemic of people, adults and adolescents alike, who lack basic proficiency, but everyone who you encounter online is the opposite of that. So in invoking the Fermi Paradox , “Where are they?”

This is further evidence of the ‘great bifurcation’ in America between the successful and highly visible of society, and everyone else. Sure, there are a lot of kids struggling with math and reading, but they tend to ‘drop out’ quickly, usually after high school. That is to say, they either don’t attend college, or if they do, generally it’s a low-ranking college and they don’t finish. They aren’t competitive in the job market either. Rather than having visible, high-status roles in society either online or offline, they are largely invisible, analogous to the concept of ‘bulk matter’ in brane cosmology [the bulk is the volume between the branes, but cannot be seen or interfaced with] or dark matter. Stars, despite being highly visible, only represent a small fraction of the total mass of the universe. The rest is believed to be dark matter, which is invisible. The same applies to society. This is why everyone seems so competent online, like on Reddit, Substack, Quora, Stack Exchange/Overflow, or on forums, yet this is apparently only a highly visible but small fraction of overall society.

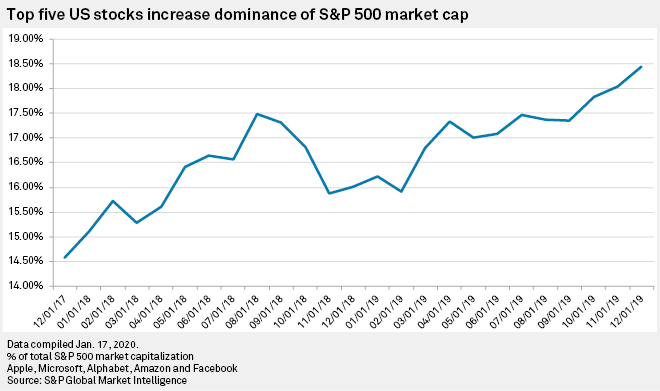

But that still leaves the overachievers, who are a small on a relative basis but are still numerous (and growing) on an absolute basis. The college wage premium is the widest ever and shows no signs of narrowing even in spite of Covid, the rise of online learning, and growing public awareness of a possible higher-ed bubble. MBA salaries have surged in recent years , in part due to a more competitive economy. The era of trillion-dollar companies means higher stakes and hence higher salaries to attract top talent, even adjusted for inflation. The size of the S&P 500 relative to GDP is at 150%, versus 50% in 1990:

As the largest companies in the world get bigger and wealthier relative to GDP, it means they can afford to pay higher salaries.

5 companies, all tech, are 19% the S&P 500:

A Harvard MBA who graduated in 1978 could expect to earn $22,000–the equivalent of $100k today. Today, it’s closer to $150-200k or more after including various bonusses:

During the past five years, HBS has continued to see rising median salaries for their new grads. On Monday, Harvard Business School announced that its class of 2021 graduates, on average, earned a $150,500 base salary, a $30,000 signing bonus, and a $37,000 performance bonus; that’s a $217,000 base salary immediately after earning an MBA from Harvard. It’s also a 14.2% increase from 2017, when grads were earning a total compensation package of $190,000, on average.

Even after accounting for student loan debt, this is a significant real return compared to 1978. [1]

In the ’60s if you were good at math maybe you got a job at NASA, Bell Labs, or IBM. But today’s career paths for smart, ambitious young people are more lucrative and higher status, even adjusting for inflation and student loan debt. Until relatively recently, there was no equivalent of the 6-figure office/professional job. Or the mid-6-figure SWE job. Today, mid-6-figure salaries for finance, law, consulting, medicine, or tech are not unheard of, but even expected, as well as other forms of wealth such as home and stock market appreciation, as well as employee stock options.

Sixty years ago, homes were not really considered investments, unlike today. For the past few decades, home ownership has been an essential part of accumulating inflation-adjusted wealth instead of pissing it away on rent, which has exceeded inflation. After the stagnation of the 60s-70s, stocks have posted strong real returns even despite the 2000-2003, 2008-2009, and 2022- bear markets, thanks in part to low interest rates and record corporate profits. Same for cheap mortgages (although mortgage rates have finally gone up). This has led to a two-fold wealth compounding effect: first from inflated salaries, and then from investing said salaries in rapidly appreciating assets.

Higher salaries, more wealth, and higher status means higher stakes, which means more competition and more optimization, such as AP courses and taking calculus in high school.

The same trend of outsized returns for a handful of individuals is also observed in the humanities and liberal arts as well, such as Substack success, viral articles, and lucrative ‘big four’ publishing book deals for new fiction authors. Freddie DeBoer makes $200,000/year with just his Substack, by his own admission, and others like Glenn Greenwald, Matthew Yglesias, Bari Weiss, and Matt Taibbi earn even more, comparable to even mid or high-level FAMNG salaries just for writing blog posts.

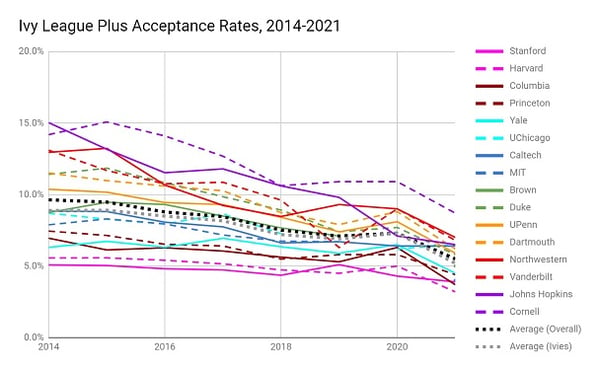

The problem is, unlike the below-average kids, the above-average kids do not ‘drop off’. They continue to compete from high school (even possibly as early as preschool, such as the insular world of high-stakes, selective elite/specialized NYC schools) all the way until grad school and the job market, with other high achievers for a relatively scarce number of slots, be it good-paying jobs or high-ranking colleges. But the number of slots for top colleges and top jobs likely has not kept up with the growth of overachievers.

Enrollment for top universities has not kept up with population growth and demand, hence lower acceptance rates:

The acceptance rate at MIT has fallen from as high as 30% as recently as 1995, to just 7% today:

If the top 1% of American high school students–roughly 150,000 individuals–are applying to colleges which have a combined and fixed enrollment of 70,000 applicants, which is the total annual enrollment of the eight schools that comprise the Ivy League, that is going to be a lot of overachievers who are left out, who may feel entitled to those spots. Indeed, it’s not uncommon to read personal accounts of seemingly overqualified applicants being rejected from multiple top colleges. A commenter from Steve Hsu’s blog recounts how his two sons were rejected from numerous colleges despite having top SAT and GPA scores and various extracurriculars:

This leads to a sort of Sisyphean struggle or red queen dilemma in which this small fraction of society is competing harder and harder, yet outcomes are possibly more unequally distributed. What happens to those who cannot cut it? What if being in the top 2% is not good enough and you need to be in the top .5%? What happens to these people who are only in the top 5-.5%, not the top .5%? Forget learning calculus, now you need to win math competitions, too. You need a GitHub repository and know Python well. A 17-year-old recently published a math paper which proved a prime conjecture. Another 17-year-old made a fully-functional app and posted it to GitHub. This is your competition now.

Today’s ‘smart kids’ would kick the butts of the smart kids of the 70+ years ago. There was no GitHub 70 years ago. Math competitions were not as high stakes (I think there was only the Putnam). Learning calculus was considered a big deal and not commonplace like it is today in high school, along with AP courses (as discussed above). Child prodigies were not as impressive either (skipping 2 grades was considered quite rare and remarkable, but it’s not unheard of today to read about even 10-year-olds going to college, although one could make a case that standards have been lowered). And likewise, the smart kids of 70+ years ago, if transported to today, would likely only be slightly above average and not in any way stand out, even Terman subjects. Now why does society feel incompetent compared to in the past. Why no second Moon mission? Or Mars mission? But this overlooks recent innovation in AI, apps, smartphones, 5g, rockets/space-X, semiconductors, self-driving cars, genomics and drugs, but this is for a separate discussion.

More student loan forgiveness and financial aid, such as Biden’s recent $10,000 student loan forgiveness proposal, will boost college attendance. However underachievers, who either drop-out or attend low-ranking schools, are likely the biggest beneficiaries of this proposal, not people who graduate from good schools, get good jobs, and are able to pay the loans off easily.

One of the great conceits of society is that opportunity is always good. If we can create more ‘access’ (a favorite buzzword), everyone benefits. But benefits how? And who? More technology, cheaper computing, smartphones, online learning, better curricula, etc. means more learning on an absolute basis, but the harder problem is not just improving one’s absolute ability but also one’s relative position. High-paying companies and good schools don’t just want applicants who are better on an absolute basis, but those who are among the best on a relative basis (which implies you are getting the best on an absolute basis, too). Obviously, this is a zero-sum game. For someone to get relatively better implies someone else must become relatively worse.

We need to stop the ride and let people get off. The mid-6-figure job is the 20th-century equivalent of the record contract, except whereas the recording industry peaked in the ’90s, which thanks to file sharing and the rise of the internet underwent deconsolidation, the opposite trend has been observed of the largest of companies, which have become increasingly consolidated in terms of earnings, profits, and market share. We have to accept lower returns to success or lower our expectations, or that there are limitations to the meritocracy. The meritocracy implicitly promises that talented, hard-working people will rise to the top, but not that the number of top spots must keep up with the quantity of talent, which is a harder thing to promise.

[1] The college wage premium is not just limited to elite-school MBAs, but includes the lowly bachelor’s degree. In 1976, starting bachelor degree holders earned on average $$7,600/year, which is the equivalent of $39,643 today. As of 2022, starting salaries for 4-year degrees average $55,000/year. Even after accounting for annual interest payments on student loan debt, this is still a $10,000/year premium compared to 1976 ($40,000 student loan debt, 6% interest over 10 years = $5,300/year in interest payments).