There as been considerable debate about the so-called ‘growth mindset’ versus the ‘fixed mindset’. Scott has written many posts comparing and contrasting the two. From the article Why Grit Is More Important Than IQ When You’re Trying To Become Successful:

While comparing career accomplishments, you were shocked to learn that the kid from school with the genius IQ, the one all the teachers thought would be spectacularly successful, had struggled with his career. How could this be, you wondered. This was the person everyone thought would invent something that would change the world.

It turns out that intelligence might not be the best indicator of future success. According to psychologist Angela Duckworth, the secret to outstanding achievement isn’t talent. Instead, it’s a special blend of persistence and passion that she calls “grit.”

Why is this even up for debate. Talent/IQ (innate factors) matter much more than grit. Grit will only get you so far. Talent measures your potential. Grit can be likened to the amount of water in a swimming pool. Talent is the depth and is a fixed property intrinsic to the pool and thus cannot be changed. No one denies hard work plays a role in success, but talent is what ultimately determines one’s rank or relative success in which effort/grit is held constant. If everyone puts in the same number of hours at a task, be it writing, chess, playing an instrument, etc., it logically follows that individuals with the most talent (deeper pools) will rise to the top.

Like most articles espousing a black-slate/growth-mindset-centric view, it relies on one-off anecdotes, poorly-executed/non-replicating studies, and reasoning that betrays even the most elementary of empiricism and critical thinking ability. The anecdote of the ‘genius-IQ kid struggling with his career’ is as vague of an example as one can conceive of. What does it mean to ‘struggle’? What was his career? Just saying he struggled is useless and tells us nothing in so far as advancing her argument. It is possible that the high-IQ kid struggled because he chose a challenging, competitive career that would otherwise be totally hopeless and unobtainable for someone of an average IQ (such as working for Google, becoming a math professor, going to a top-rated law or medical school, etc.).

Even in elementary school, long before anyone can put in their ‘10,000 hours,’ teachers can readily identify individuals who have the most potential to be successful, and then those individuals tend to rise to the top in terms of earnings potential later in life or creative success. A 7-year-old who is composing creative writing stories at a 14-year-old level probably stands a good shot a being a professional writer, at least compared to a 7-year-old who cannot even read. A 10-year-old who takes to calculus probably has a much better shot of becoming a mathematician (or getting any high-paying STEM job) than a 10-year-old who struggles with fractions even after having it explained to him repeatedly.

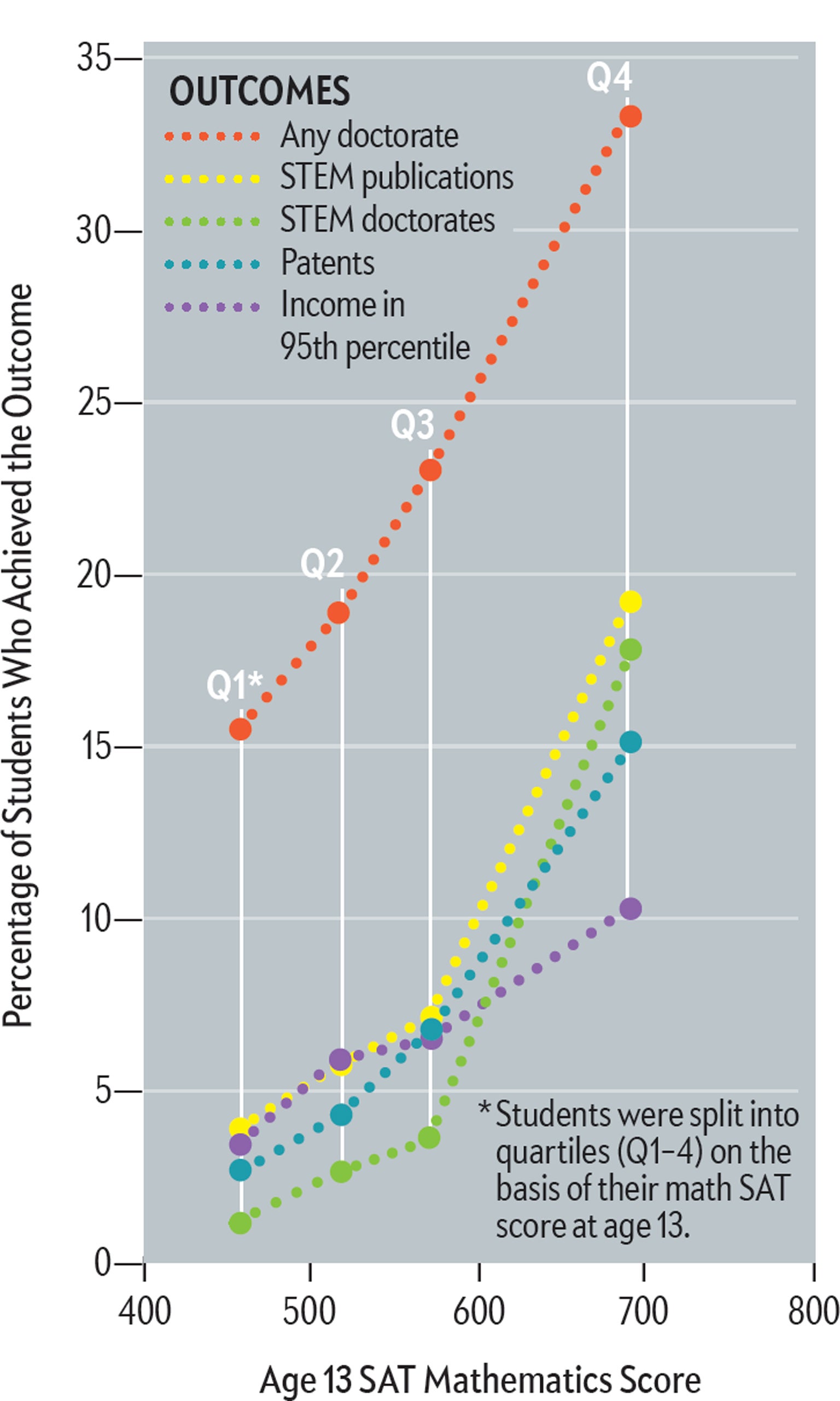

This is confirmed by quantifiable data: 13-year-olds with very high math SAT scores, the top quartile, are much more likely as adults to produce creative work, publish in a journal, obtain a patent, or get a STEM doctorate compared to the individuals in the bottom quartiles:

Professional writers by in large exhibit talent long before they achieve career success, but in confusing correlation with causation, such success is often mistakenly attributed to grit by the media and pop psychologists, ignoring the role of talent. Very seldom does someone just stumble upon exceptional professional or creative success later life without some clues early in life suggesting at least some above-average innate ability. Elon Musk was coding at the age of 12. He got a lot more ‘mileage’ for this grit than someone who works in retail. Winston Churchill was a brilliant student before he became a brilliant leader (the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, notwithstanding).

Just to give an anecdote, my junior high school had a writing competition, and the winners were so much better than everyone else which became apparent when they read their stories aloud, that it could only be explained by talent. It was not like everyone had years to practice, but such ability could have only been divined in some way, not taught. Same for the math competitions, in which the winners were so much more overwhelmingly talented than everyone else, that no amount practice could ever suffice to close the gap. People with talent are simply able to just ‘do’ things at a level that is completely out of grasp of everyone else, in much the same way a magician defies our preconceived notions of physics, except it’s real.

The talent-deniers are quick to point out that some talented people ‘burn out’ later in life and fail to live up to their potential, but, by in large, high-paying, prestigious professional jobs are overwhelmingly filled by people of at least above average intelligence. If someone aspires to have a good-paying, prestigious job, such as in tech, they will likely encounter tough competition from smart, hard-working people vying for those jobs, not the ‘burn outs.’

We like to lie to ourselves by saying that grit matters more than talent, or by knowingly falsely ascribing our own or someone else’s success to grit, because that is what feels good and is the socially-acceptable thing to believe, but deep down, we know that talent matters more. I am sure most parents would prefer to be told that their kid is smart, than hard-working. The meritocracy creates a lot of opportunity but also inequality. So perhaps it is comforting to just attribute such inevitable inequality to environmental factors, which can be fixed with policy, good intentions, or ‘better parenting,’ than innate factors, which are fixed and thus more impervious to such solutions. It is not so much what we aspire to greatness (or some idealization career success), but that we want to believe we have the potential for greatness, and failure to live up to those expectations must be attributable to some some attribute that is at least in one’s control (such as grit) than something that is not (IQ).

Perhaps the growth vs. fixed mindset is a false dichotomy that overlooks other important variables that are neither, such as favoritism, connections, and luck/timing. One can argue that talent and grit are necessary but insufficient conditions and you also need that third variable: luck.

So what is the answer? The cold dose of the fixed mindset, or the comforting affirmations of the growth mindset? There is none, unfortunately. The growth mindset sets people up for failure, but telling someone, particularly a child or a young adult, point-blank they cannot or should not do something because it would be a waste of time, is also bad because it is demoralizing and a blow to one’s self-esteem even if it is the prudent thing to do.

Given the truth of this. Whatever legitimate position people find themselves in due to talent. All deserve dignity and not to be despised.

Those who do low IQ Blue Collar Work because they are low IQ shouldn’t be looked down upon as lazy or as worthless. They can’t help their station and it isn’t their fault. Let each have their station and it’s unique Dignities.