It’s not news that Americans are increasingly divided along party lines. Democrats and republicans may as well be entirely different species, let alone disagreeing on issues. But why is this?

538 notes that there is is very little crossover support between parties, meaning that republicans and democrats more strongly than ever disapprove of their respective ideological opponents, as depicted by the graph below:

This lack of crossover support for presidents in their first term in office points toward one of the most animating forces in American politics today: Increased disdain and hatred of one’s political opponents, known as “negative partisanship.” As the chart below shows, opinions about the other party have become far more unfavorable since the late 1970s. In other words, it’s not that surprising that Americans are far less likely to approve of — and more likely to intensely dislike — presidents from the other party right from the moment they take office.

So starting around the early to mid 80s, the divergence began.

Also, the approval/disapproval ratings of Obama, Trump, and Biden (first 5 months) remained remarkably steady throughout the entirety of their terms, usually within a 4-6 point range. Trump’s approval rating oscillated between 37-43% range, even in spite of major stories such as Covid and BLM protests, never exceeding or falling between this range. Same for Obama, whose approval rating hovered between 47-53% despite major stories such as the killing of Bin Laden and the passage of Obamacare.

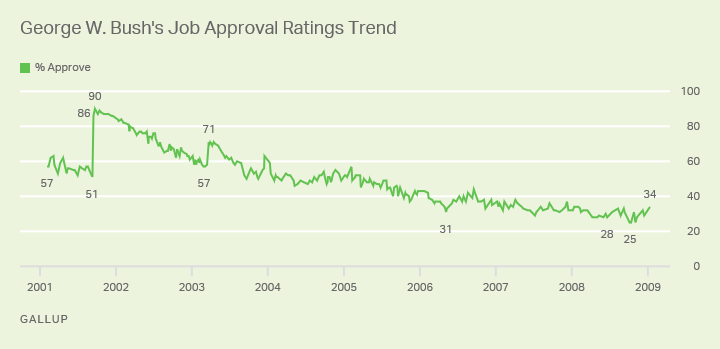

This is even more remarkable when one considers the major forces at play–the media in particular–that are trying to sway public sentiment, yet in spite of multi-billion dollar media budgets and armies of pundits and journalists, no side is able to decisively claim a supermajority of public approval. The last time this occurred was after 911, when Bush’s approval ratings shot up to around 70-90%, until until steadily falling to around 25% when he left office.

So what is happening is, increasingly divided politics and sentiment is correlated with the stability of presidential approval ratings. This suggests that fixing or mending such division, somewhat unexpectedly, means having a situation in which the majority of the public either really strongly approves of the president or really strongly disproves. I remember in 2007-2008 it felt like there was less division because everyone seemed to be in agreement that ‘Bush was bad’. For the final three years of Bush’s presidency, his approval ratings were consistently 10% lower than that of Trump, at around 25-40%:

Going back to the above graph, what happened in the 80s? That was the last time there was a major electoral blowout, with Mondale in 1984 losing in a massive landslide to Reagan, who got about 59% of the popular vote. And before that, there was Nixon, who in 1972 won 60% of the popular vote against McGovern, and then, in 1964, LBJ got 61% of the popular vote against Goldwater.

You have to go back 35 years to find an election that was as lopsided as 1984. Since then, election have continued to be close, especially in the popular vote. No president since, including even Obama in 2008, has come close to achieving the sort of blowouts that Nixon, Johnson, and and Reagan did.

Both parties seem to have gotten better at running effective campaigns and selecting effective nominees, instead of ‘losers’ like Mondale, McGovern, and Goldwater. An increasingly effective ‘political machine’, in conjunction with huge media budgets and aggressive campaigning, means closer elections.

But close elections may be symptomatic or a cause of increased division. An election that is too close, like in 2000, means that the losing side will be more inclined question the legitimacy of the results and the democratic election process in general, sowing division and distrust, like we see now regarding alleged fraud in the 2020 election, or even during the 2004 election. A blowout election is more likely to inspire confidence in the democratic process, because the losers can attribute their loss to a poor choice of candidate or other factors, than the process itself being broken.

An exceptionally bad, unpopular candidate is like a villain in a movie, so his defeat is more of a catharsis than an emotionally draining and morale-crushing loss. Or an exceptionally boring, uncharismatic, or dispassionate candidate, like Romney, Carter, or Mondale, may also help, because the losing side is less likely to become emotionally invested in the outcome. In 1996, 2008, and 2012, there was never such a strong attachment for the losing candidate like we see now with Trump, who is considered to still be the de facto leader of the party and president by many of his supporters, but the GOP and the public treated Dole and Romney like a bad memory, to be repressed and forgotten. Same for Gore in 2000, who the left and the media pretty much forgot about immediately after he conceded following the lengthy Florida recount process. Periodic extremely lopsided elections, like in 1964 or 1984, is probably what America needs to return to a less divided time.

You miss an important point: what America needs is legitimate elections.

None of you have established that Joe Biden, a centrist, stumbling, nonentity geezer only a few years away from full blown dementia, actually got the most votes out of any candidate in history, including the mulatto messiah Obama and the first woman president because we said so, Hillary.

It is a good point . I was suprised as well he got so many votes.