Are we in the best of times or the worst of times? Is the ‘vibecession’ real, or are people just venting frustrations? I am of two minds here. I agree with Zvi that things have gotten better or are the best by many objective measures. People have near-unlimited entertainment choices. Cars are safer and more reliable. Less food spoilage. Lower child mortality rates. More medical advances. Air conditioning is a huge one. Not too long ago, people not uncommonly froze to death during the winter or sweltered in the summer heat.

But there is also the ‘vibecession’ phenomenon, as Scott discusses in his viral article, “Vibecession: Much More Than You Wanted To Know”. On a related note, the scapegoating of ‘boomers’ for perceived economic difficulties is another trend, which as Scott in a follow-up article “Against Against Boomers”, he argues such blame may be misplaced: according to his analysis, boomers didn’t actually have it easier compared to subsequent generations.

Overall, by many objective measures, things are going well, yet things feel off. Invoking Dickens, we are in the best of times and the worst of times.

I blame increased difficulty and competitiveness of modern society. ‘Higher standards of living’ is contrasted or juxtaposed with how things also feel harder than ever. It’s not so much that times are bad or that the economy is weak, but that in many respects the economy and society is much harder due to increased competitiveness and screening. These are mutually inclusive, in how society is becoming better/richer and harder at the same time. It’s little consolation to have ‘more Netflix choices’ or a faster iPhone, when tuition, housing, or healthcare is so expensive. Or people’s careers feel so stagnant.

For example, there are more roadblocks and other screening to being hired than ever before, for all skill levels of work, such as personality tests, multiple interview rounds, phone interviews, drug tests, background checks, and so on. Employees and applicants are viewed as a burden, incompetent, and presumed to be morally defective. A popular meme is how being hired means having to pass HR, as Scott noted:

As I noted in “The Lost Generation”, it’s not enough to just blame diversity or affirmative action for whites falling behind. There is too much competition for these prestigious, high-paying jobs–whether in finance, journalism, tech, academia, or elite college admissions. Too many smart, competent people are vying for too few slots. Hence, a lot of people are excluded despite being objectively qualified on paper, more so than predicted only by racial favoritism. Moreover, ‘smart Americans’ have to not only compete with each other, but also worldwide talent and now AI.

Zvi blames unrealistic or inflated expectations for young job seekers, who expect to earn $500k. I disagree. From what I ascertained on Reddit and elsewhere, young people are struggling to find jobs regardless of pay or qualifications. Too many applicants and screening again. So in this sense, the bad vibes are not unfounded.

Another example of ‘things becoming too hard’ is publishing math, as someone with experience with this. From the ’50s to even as recently as the ’90s, many math papers were terse and incremental, typically expanding on a single idea or developing a new technique. Many of these papers were short (5–10 pages) and could be produced at scale by academics seeking tenure, who needed enough publications to please the deans and review committees. Fast-forward to the 2000s, and there is much more competition, and rejection rates for top journals have surged. If you’re lucky your paper will be rejected fast, or unlucky held hostage for 8-12 months by editors until finally rejected.

But there is room for optimism. In regard to tuition, the reality of the situation may not be as dire as the data may suggest. The actual tuition paid (net) is typically only 50% of the ‘quoted sticker price’. Hardly anyone is actually paying $50k/year on tuition even if the data says so. Although tuition has surged, so have wages for white-collar workers. After taking into account cheap borrowing for federal loans, scholarships, and other aid, and college grads come out way ahead still.

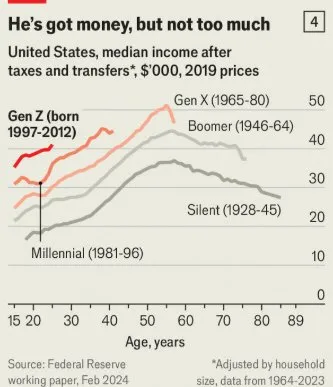

Monthly student loan payments are tiny relative to salaries for white-collar jobs. True, this is contradicted by the difficulty of finding work, but for those who do, the data is favorable. Similarly, as Scott notes below, gen-z and millennials are ahead of earlier generations controlling for age, writing “Just as our previous graphs imply, Millennials and Zoomers earn significantly more than Boomers did at the same age, even in inflation-adjusted dollars.”

I attribute this, in part, to inflated white-collar salaries post-’08 and post-Covid, combined with post-’08 asset inflation in stocks and real estate, thanks to a tailwind of accommodative fiscal and central bank policy on an unprecedented scale. The fed pulled out the stops in ’08 and during Covid to prop up asset prices.

During the ’90s and early 2000s, often regarded or spoken with a nostalgic fondness as ‘the best of times’, there was no such thing as the ‘mid-six-figure white-collar salary’ as seen today. Earning ‘a high 5-figures’ was seen as ‘making it’ back then. Interest rates were so high for much of the ’80s and ’90s, making mortgages expensive. Home values didn’t appreciate that much either in real terms. The notion of homes as a piggy bank or ATM didn’t really exist.

Astute commenters, as seen on Reddit and on Substack in response to Scott shown below, are not easily assuaged by nice graphs. Such optimism is juxtaposed by a job market that is more cutthroat than ever, with tons of rejections for qualified applicants, as many users on Reddit and other social media can attest. Securing an interview or callback is hard enough, let alone an actual job. The words “sorry”, “regret”, and “unfortunately” are a familiar sight to any job seeker.

Or in regard to housing, true, homes are bigger. But as many observed, there is also the ‘ladder-pulling effect’ of older people who secured cheap homes, and now today’s gen-z in HCOL areas are literally priced out, with renting or sharing as the only options. ‘Bigger homes’ does not solve the problem of affordability for existing homes.

Another way to square ‘vibes’ with Scott’s optimism is that life looks great if you’ve already “made it”: your pricey HCOL home is surging, and your high-paying white-collar job is funding your large nest egg. Your monthly student loan payments are tiny relative to your large monthly income. But getting to that point requires clearing many hurdles and most will never get there.

So in answering if things are easier or harder, I think it’s more situational. Excluding positional goods, Americans today are objectively much better off in terms of standards of living than kings of centuries or millennia ago. John D. Rockefeller is ‘poorer’ in many respects than the middle class today. But the king obviously has much more status, which is nice too. Invoking Maslow’s hierarchy, when times are good and essentials are met, people want status, as seen today. And when times are bad, people want essentials. The king who fell ill would trade his kingdom for Penicillin. But Penicillin cannot be traded for status.

In conclusion, in agreement with Zvi, regarding ‘vibes’, the actual complaint, I posit, is that “things feel too hard,” probably due to too much competition (so-called ‘elite overproduction hypothesis’) and unreasonably high standards (e.g. excessive job screening, credentialism), which does not contradict that society at the same time is much richer and technologically advanced.