Every indicator points to the rise of a post-work, post-scarcity economy, such as forecasts of ‘hundreds of millions of jobs’ lost to AI, or discussions of 4-day workweeks, which have being tentatively tried with success. Famously workaholic Japan is pushing for 4-day workweeks due to labor shortages. Or some cities implementing small-scale UBI programs. Open Research Lab has completed the largest study of UBI to date. Or the trend of companies ‘doing more with less’, such as mass-layoffs of otherwise immensely profitable tech companies. Or an increasing number of holidays, such as Juneteenth.

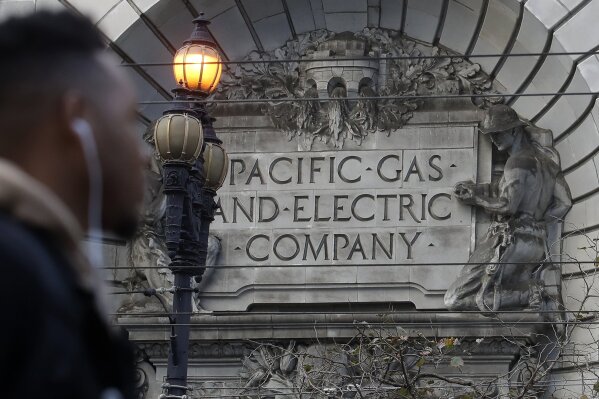

During the early to mid 20th century, manpower was scarce due to wars and rapid economic expansion and infrastructure outlay, such as electric grids, dams, trains, and highways, all of which necessitated a lot of manpower to build and operate. Work was also also object of pride. People identified with their profession, even literally, such as occupational surnames (e.g. ‘Mason’ or ‘Skinner’). Union jobs were much more common relative to the size of the labor force, and not only provided lifetime employment, but also conferred a sort of identity or community that went beyond just collecting a paycheck. Unions also wielded immense political power. Culturally, society seemed to valorize work, such as sitcoms and movies of the era which depicted the putative breadwinner ‘going to work’, as if this was the expected or the right thing to do. This appreciation was also signified in the architecture itself, such as engravings of electricians in the facade of an old PG&E building:

The late 20th century saw the rise of the middleman or ‘desk job’, in which instead of purposeful work or work in which the end-product is directly downstream from the job itself (e.g. building a dam), there is a detachment from the worker and the finished product, or the social or economic value of the job itself is less obvious. The Atlantic recently published a viral article describing white-collar work as ‘nothing but meetings’. Much of modern work is about solving coordination problems, like getting two different teams or groups to achieve a single goal or overseeing teams of employees who may not even reside in the US.

I think lot of workers get the sense that their jobs are pointless or unappreciated, alluding to the ‘bullshit jobs‘ phenomenon, popularized by the eponymously-titled 2018 book by the late anthropologist David Graeber. If you’re someone involved in machine learning or language models, you’re not only making a good salary, but also making a difference in ways that appear to be valued by society, but many workers see themselves as nameless or faceless cogs whose contributions go un-thanked or unnoticed.

Just as there is an uncanny valley in terms of animation or robotics, there is an uncanny valley of success, or a sort of barbell phenomenon in terms of labor. If you are really successful like Elon Musk, Taylor Swift, Tom Brady, or Sam Altman society will worship you, and work is seen as a lifestyle or a calling. Despite having enough money to last lifetimes, professionals in law or business never seem to retire. Work provides socialization with other elites, and the job title confers status for those people above the masses, so who wants to give that up by retiring, even if it’s the right thing to do and job performance suffers. But otherwise, work is seen as a chore or purely transactional or impersonal…’going through the motions’ as it’s called.

Today’s elite need to be dragged kicking and screaming into retirement. Joe Biden’s mind retired a decade before the 81-year-old former Delaware Senator handed off the baton to his running mate, Kamala Harris, whose opponent, Donald Trump, 76, is not too far behind. Indeed, the percentage of Congress over 70 is the highest ever (although some of this can also be explained by increased life expectancy):

Microeconomic factors also play a role in the apparent decline of work, such as increased barriers to work. The era of ad hoc work is long over, in which able-bodied people could just show up at short notice to fill a vacancy. Even the simplest of jobs require interviews and detailed background checks. In talking out of both sides, companies say they need work, yet applicants have to clear more hurdles than ever before to be hired, including interviews, background checks, and other screening, analogous to the careful process of selecting a new Pope or a Supreme Court justice. Yet we’re talking flipping burgers or operating a deep fryer , not trying to interpret a priceless legal document that was written 237 years ago or getting into Juilliard. I can understand how some screening is necessary, due to the difficulty and legal risk of firing employees, or the risk of hiring bad employees, but it has gotten out of hand.

“@Casagrandezz” is right. Companies don’t want to bear the risk and cost of training:

Disagree know many healthy & educated mid 20s people who can’t find a decent job because the job market overweights experience, underweights raw horsepower & youth & exaggerates how difficult “training” new employees & entrants is (takes 2 months for decently smart ppl) https://t.co/QVWfgIWcUr

— HB (@Casagrandezz) August 26, 2024

The US labor market is in a weird sort of place in which labor is very expensive, yet Americans feel underpaid due to high inflation and expenses such as healthcare and rent, so the result is chronic labor shortages and workers feeling squeezed. By comparison in less developed countries labor is much cheaper.

In terms of macro factors, during Covid, firms realized that they can cut back drastically on labor without hurting sales. This is why at many restaurants and coffee shops the hours have been shortened considerably (this also saves money by not having to provide full-time benefits). It’s not uncommon for a single employee to occupy the roles of making orders and taking them, not uncommonly resulting in long wait times and poor service during peak hours, which apparently customers are fine with, as the practice has persisted and not hurt sales. Sometimes even three roles, like washing dishes. It has gotten ridiculous, and I find myself eating out less often due to the atrocious service, which I guess my waistline and wallet thank me.

Pre-Covid, in hindsight, restaurants were leaving a lot of money on the table by either not raising prices aggressively as we’ve seen now, or by not gradually cutting portion sizes and hoping customers don’t notice, employing too many staff, or staying open too long (or at all). Conversely, in less developed countries, the customer service is excellent for those who are able to pay a little extra, like tipping. Covid was like a forced experiment that shaped the concept of work in ways that will be felt for a long time to come, likely permanently, whether it’s work-from-home or the rise of gig work like Door Dash. Stores can shorten their hours and make up the difference with delivery, for example.

Culturally, the NEET phenomenon is further evidence of the decline of work. A growing percentage of young people are disengaging from the economy. Many men are ‘dropping out‘ or not working. Rather than starting families or aspiring to a high-maintenance consumerist lifestyle like their parents, a not insignificant number of gen-z and millennials are content to a low-impact life of video games and other leisure. This isn’t the same as the Hikikomori phenomenon, which describes individuals who withdrawal from society, but more like being idle or the voluntary early retirement of able-bodied individuals. It’s not like you need to work that much or save much money if your lifestyle is low-maintenance. To quote Office Space, “You don’t need a million dollars to sit around and do nothing.”

Perhaps having to comply with onerous pre-employment screening, political correctness, an emasculating work environment, and bad bosses and bad customers is not worth the low pay. Maybe DEI and diversity training are tolerable if you’re making mid-six-figures, but is a less attractive value proposition for those who are just above minimum wage. Why does being a physicist mean having to pledge loyalty to a diversity statement, instead of doing the best physics possible. I can understand how workers have grown frustrated of this. Baked into this is the implicit assumption that men are inherently prejudiced and need to be reeducated. Or why men are skipping college or dropping out, instead of going tens of thousands of dollars into debt to be lectured about ‘critical theory’ when a decent job may not even exist after graduating. I don’t want to make this too political, but I don’t think the role of politics can be denied in so far as these trends are concerned.

Also, there are many alternatives to traditional salaried work that decades ago did not exist, such as gig work (e.g. Uber Eats or Door Dash), content creation (e.g. Patreon), or social media (e.g. promoting products on Instagram). Young people today have a miscellany of side hustles and gigs that can fill the gaps of long stretches of unemployment. No niche is too small or esoteric: even math videos get a lot of views and presumably a lot of ad revenue on YouTube, like 3blue1brown. Like to eat? That too is covered.

The rise of ‘van life’ videos is part or symptomatic of this trend, but unlike the motorcycle culture of the ’60s and ’70s, is how persistent and permanent it seems. Rather than escaping for a few years to find oneself, it’s the end point. People expect to make careers out of this, and remarkably many have. It satisfies the criteria of what an ideal job ought to provide : purpose, autonomy, and community (that being other van-lifers). That is, except for practicality. Like joining the circus, this is not an aspiration that exactly scales well. This means a lot of trial and error to find a niche or hustle that eventually works.

In alluding to the barbell phenomenon above, young people who have a lot of aptitude and talent tend to be more ambitious in the hope of rising up the ranks. But those who are somewhere in the middle or bottom in terms of talent or sought skills (like coding), or have resigned oneself to a lifetime of mediocrity, drop out or do the bare minimum. Why try, especially if post-scarcity and UBI become realities? Will such a thing as a middle class even exist a decade from now?

I think this skepticism or uncertainty about the future also explains how there are two extremes in terms of how young people handle money, based on diverging perceptions of the future and economic realities: for those without good jobs or sought skills, gambling becomes attractive as an ‘all or nothing’ shot to get rich, because opportunities are otherwise so limited. But there is also some optimism that maybe UBI or other assistance will prevent one from hitting rock bottom. This was seen in 2021-2022 during Covid, in which many 20-somethings gambled their stimulus checks on ‘meme stocks’, crypto, or other speculative investments at the time. For the same reason people play the lottery, it’s not always that innumeracy is to blame, but that the very act of playing and the hope of winning provides an escape from the dim reality of one’s predicament.

But on the other extreme, for those with good jobs, saw the post-Covid surge of the ‘FIRE movement’, in which frugality is the objective. The more money you earn, the more you can make through passive compounding with investing–a Mathew effect but applied to wealth–which creates an incentive to keep accumulating wealth.

The biggest conceit in the labor debate is blaming a lack of talent. How does a talent shortage explain a labor market in which many people are seemingly overqualified for tech jobs, or that tech companies are inundated with highly-qualified applicants, or that many qualified applicants often get rejected, some from top schools and with lots of experience. Despite as of Dec. 2023 the lowest unemployment rate in decades, finding a job is still really hard:

The issue is insufficient demand or elite overproduction, not a lack of talent. Compare the Cold War era, when think tanks and large companies such as Bell Labs, a then subsidiary of AT&T, paid lots of smart people the then-equivalent of an upper-middle-class salary to just sit around and brainstorm, compared to today when much more is expected from employees, like having to meet deadlines and quotas. Meanwhile, not surprisingly, on an inflation and per-employee basis, profits have surged.

Work is typically viewed as necessary for self-sufficiency and individual economic well-being. But in an economy dominated by trillion-dollar tech companies and surging private sector/household wealth, such as real estate or stocks, potentially creates a huge wealth trickle-down effect in which work may be unnecessary for those who benefit downstream. The Nasdaq 100 and the S&P 500 since 2009 has on average returned 20-30%/year, which vastly exceeds inflation (2-5%/year) or population growth (1%/year), making the average person wealthier and the nation wealthier collectively (although such wealth is still highly concentrated).

On a long enough timeline, or, as alluding to Thomas Piketty, as r > g, it stands to reason the probability that someone knows someone (e.g. a family member or friend) who is wealthy, like with Nvidia or some other investment, approaches 100%. Invoking Dunbar’s law, everyone will be a degree or two away from knowing a wealthy person. So instead of going to work, you can live with your friend whose uncle owns .05% of Google.

The top of the Forbes 400 list is dominated by tech billionaires, with a combined personal wealth of over a trillion dollars for the top 10. Although though such wealth is highly concentrated now, the capital eventually has to go somewhere–such as taxes, and the rest disbursed to families and charities. Automation means more corporate profits, which enriches shareholders, and then this capital is slowly spread out. Or to put it another way: a surplus of shareholder value from underpaid labor or automation is eventually redistributed more equitably, but it takes longer and indirectly.

Dubai and other oil-producing nation-states are microcosms or case-studies of this phenomenon, but with oil instead of tech stocks. Large percentages of the Emirati native population does not work, due to oil profits funding an expansive social safety net. The difference here in the U.S. such a safety net is funded by private individuals and charity. This can be windfalls, but also publicity stunts like some of Mr. Beast’s videos in which he gives away money. For this reason, I predict the post-scarcity society will be funded by voluntary charity from the windfalls of capital gains, in contrast to a comprehensive federally-funded UBI, although state or city-level UBIs may become more common.

This is already happening, such as huge inheritances and other forms of trickle-down wealth. In what has been called ‘the great wealth transfer’ Boomers stand to bequeath over $90 trillion to their children over the next few decades. Many of these so-called ‘social media influencers’ are in fact just living off their parents. This will become increasingly common in the coming years.

As “@MurrayHillBro22” notes:

It’s crazy how many of my late 20 year-old and 30-something friends receive monthly financial assistance from their parents.

Is this a modern development or has it always been like this?

— Murray Hill Guy (Alpha) (@MurrayHillBro22) September 10, 2024

There are possible downsides though. Work is not just about money as it is about control over one’s time and independence. Ironically, work can be liberating. I recall when I was self-employed or not working that no one seemed to respect my personal time. People assumed that because I was not working at a ‘regular job’, that my time was not that important or that I should have been ‘up for anything’ at a moment’s notice. There was no delimiter between ‘my time’ and ‘other people’s time’. With a J-O-B, suddenly you have an excuse for not always having to be available. “I have to go to work” or “I have a meeting” is a great excuse and preferable to unwanted social impositions, and everyone can relate having to this; no one wants to be responsible for someone being fired by being late to work. And then after work, people will also relate that you’re tired or need some ‘alone time’. Hence, the post-scarcity society comes with a cost of not being able to establish social boundaries, which is one of the hidden or overlooked benefits of work.

Same for adult children moving away from home for work, and later to start families. Having a job, for this reason, often marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood and ‘independent personhood’, even if parents still provide financial assistance. A post-scarcity or post-work economy thus may mean a lot of adults living in a permanent state of quasi-adolescence, never able to get their lives together or failing to launch, in alluding to the NEET phenomenon earlier. Fertility rates will likely also fall as a result.

This is not to say all work will go away. Many professions will remain insulated from automation or outsourcing, such as service-sector work and hospitality, even despite a lot of people not working or staff shortages. There will also always be a need and a premium for outlier talent. If you’re the type of person who can win math Olympiads or are otherwise exceptional in some way, there is a definite path to the upper-middle class and beyond, that may even survive artificial intelligence. NBA players do not have to worry about robots taking their jobs. Nor does someone like Joe Rogan or Mr. Beast. (Although maybe I spoke too soon about math Olympiads.) An aging population will mean lots of demand for nursing homes, doctors, and at-home care. Or lawyers and financial advisors to deal with things like estates, wills, insurance, annuities, and so on even if some of these jobs can be automated.

Much of work is about dealing with all the shortcomings or limitations of technology when confronted with the complexity and unpredictability of how humans use it. Despite the ubiquity of online vacation booking and online banking, employees are still needed for customer service or in-person transactions. Although the AI doctor may use its vast knowledge to diagnose you, it cannot perform a colonoscopy or operate a surgical machine. The AI lawyer cannot represent you on the stand.

Sure, the prospect of people competing in online stunts to pay the rent sounds dystopian, or the apparent loss of personal independence by relying on charities or family or friends for subsistence, but is this worse than a lifetime toiling away at a dead-end job just to make end’s meet? Or people not having any free time or leisure due to always having to work? How much autonomy does work really provide if you’re still dependent on your boss, who is dependent on his boss, all the way up the food chain?